New Page

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY

CENTRAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL LIBRARY

D.G.ß. 79.

CO CHIN SAGA

Îierala ïlaiden

CO CHIN SAGA

A HISTORY OF FOREIGN GOVERN VIEW T AND BUSINESS ADVENTURES IN KERALA, SOUTH INDIA, BY ARABS, ROMANS, VENETIANS, DUTCH, AND BRITISH, TOGETHER WITH THE PERSONAL NARRATIVE OF THE LAST ADVENTURER AhD AN EPILOGUE

BY

S IR ROBERT BRISTOW, C.I.E.

firth a preface by

the Rigat Honourable Sir ampes Ar g, P.C. , E.C.B.K.C.S.I.

CA S SE L L- L O N D O N

CASSELL & COMPANY LTD

3} Red Lion Square

London, W.C.i

and at

zio Queen Street, Melbourne, a6t 3o Clarence 5treet, Sydney; 2q Wyndham Street, Auck- land; io68 Broadview Avenue, Toronto 6; P.O. Box *75, Cape Town; P.O. Box i i i 9o, Johannesburg; Haroon Chambers, South Napier Road, Karachi; i i/ 4 Ajmeri Gate Extension, New Delhi x; i $ Graham Road, Ballard Estate, Bomßay i; i2 Chittaranjan Avenue, Calcutta i 3; P.O. Box z3, Colombo ¡ Denmark House (3rd Floor), 8q Ampang Road, Kuala Lumpur; Avenida 9 de julho i i38, Säo Paulo; Galeria Giiemes, Escritorio 4f 4159 Orida i65, Buenos Aires; Marne 5b, Mexico 5, D.F.; Sanchin Building, 6 Wanda Mitoschiro-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyoi s7 rue blonge, Paris 5e; z5 Ny Strandvej, Esper- gaerde, Coperihapen; Beulingstraat 2, Amsterdam-C; Bederstrasse i i, Zürich z

GSHTRAL

Hi,Ni WJ

ELHl

°^+''^EoLocit;gq

Printed in Great Brsiain by Richard Clay and Company Ltd.

Bungay, Suffolk.

F. i y9

PREFACE

T

HIS is the story of the birth and growth to maturity of a project for a major deep-water port on the Malabar coast of Southern India, or rather in the sheltered waters between

that Coast and the chain of low islands to its seaward. The scheme had to overcome considerable engineering doubts and difficulties; moreover it could only come to fruition after agreement by four separate authorities—the States of Travancore and Cochin, the Province of Madras, and the Government of India. In the end it did succeed, and success was due in great measure to the skill, persistence, and faith of Sir Robert Bristow, the author of this book. Naturally Sir Robert devotes much space to his conquest of technical scepticism and obstruction and to his persuasion of the four contending parties into a working agreement—with the help, as he says, of some resourceful allies and influential sup- porters, not the least among these being the late Lord Hillingdon. Like others who went to serve in India in middle life, he was irked, almost beyond endurance, at having drummed into him ‘the pace of India is the pace of the bullock cart’. He and they can find consolation for former frustrations in the thought that a space rocket out of control is even less likely to arrive at any pre- determined destination than a bullock cart. And since i s47 India’s course seems to be set on modernizing itself at breakneck speed, largely at the expense of simple nations of the West who combine genuine good-will for the people of India with a hope that they

will, in gratitude, resist being sucked into the Russian orbit.

Two of the factors which slowed up India’s economic develop- ment between i8f 8 and •s47 were the guarantee in Queen Victoria’s proclamation not to interfere with social and religious customs, and the assurances of a large degree of independence contained in the series of treaties with individual Princes. Since

*947 the treaties have been swept away and the States have been incorporated into the new India, so that they no longer have any power, obstructive or otherwise. As regards social and religious

customs I have no doubt that many of the former leaders of Hindu V

PREFACE

thought, including Mr. Gandhi, would regard with misgiving and even distaste hIr. Nehru’s policy of going all out to make India into a secular industrial nation. And I suspect that there is, beneath the surface, a good deal of disquiet about it to-day, particularly as the growth of food production is doing no more than keep pace with the increase in population. However, Mr. Nehru is supreme and unshakeable as long as he lives. It is well known that he has on occasion expressed admiration for the material achievements of Soviet Russia. I wonder how he enjoys seeing a Communist Government in office in the very part of India which Sir Robert Bristow’s port of Cochin was created to serve.

4th January, i pf p

P. J. GRIGG

VI

CONTENTS

PREFACE. By the Right Honourable Sir James Grigg,

Page

P.C., K.C.B., K.C.S.I.. . . . v

INTRODUCTION

ACkNOWLED GEMENTS .....

, xi

. . XV

PART ONE—A PORT HISTORY OF z,Joo YEARS

Chapter

i ROMAN AND PRE-ROMAN

i ROMAN AND PRE-ROMAN

Ports and Pirates. Commerce and Culture. Rulers and Peoples

z ROMAN AND POST-ROMAN . I §

How Rome Found Muziris, and what it Found. How Rome Fell, and Why. And what Happened After

- THE PORTUGUESE IN INDIA . >7

- THE DUTCH IN COCHIN 4+

Rise and Fall. Lure of Big Profits. Intrigue and Ignominy

THE BRITISH I N INDIA (I TOO—I 20) 49

Creation of the East India Company and the Assumption of Direct Rule by the British Government in i 858

- THE COMING OF COCHIN AS A MAJOR PORT .

The Parts Played by His Excellency Lord Hillingdon and a Government Officer

PART TWO—A PERSONAL NARRATIVE

- BRIDGE OF ADMIRALTY

- RIDING THE BAR . 77

BARS AND JARIBAS 7

IO CURRENTS—AND UNDERCURRENTS ...

IO CURRENTS—AND UNDERCURRENTS ...

vii

Chapter

Chapter

I I UNDER MAY . . • • •

Page

1 2 THE MESWARnM PROBLEM .

. . . I2§

- TALES BY THE MAY ... • .

THE MAY OF A HARBOUR ENGINEER

THE MAY OF A HARBOUR ENGINEER

i f T vAIL AND TRIUMPH

i f T vAIL AND TRIUMPH

i 6 A LONG AST AND A CURE FOR ACUTE NEURAS—

THE NI A .... • • ..

PART THREE—THE FOURTH-STAGE PRELIMINARIES

17 THE BEG IN NI NG OF THE BATTLE • • .

Conferences and Rivalries. Schemes and Schemers

'39

*73

*79

i 8 C ONCEPTI ONS AND INFLUENCES ...

. I 8p

Designs and Estimates. Social Environments and Agreements

ip THE Loss STRAITS p8

Afore Conferences and Questions. Customs Dues and Dia- grams. Jurisdiction and Works and 'That Mud-bank’

zo TEAhIWORK AND ITS REWARDS . . 20$

The End of the Old and the Beginning of the Nez•. Domes- ticities, \Var, and Finis.

PART FOUR—EPILOGUE

I NTROD4'CTI ON TO EP ILO GUE . . . 22

z i THE PAL INDIA 2

marriage, Education, Work, Religion, Legislation, Industry, and Commerce. Conclusions

22 LI GI ON . • . . • • • . 2 4

Sri Aurobindo and his Exposition of Modern Hinduism

z3 THE STORY OF 1 94* 5

z3 THE STORY OF 1 94* 5

The Latest Phase of the Cochin Saga

INDEX

INDEX

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Facing Page

Kerala Maiden . .. frontispiece

The dredger Lord Hillingdon returning to harbour .

Close-up v’iew of the discharge end of the dredger’s pipe- line

The dredger’s pipe-line discharging full bore

Floating out one of the completed girder spans of the road- rail bridge

The test load of the bridge supports

The road-bridge, with the lift-span raised and the Lord Millitigdon passing through

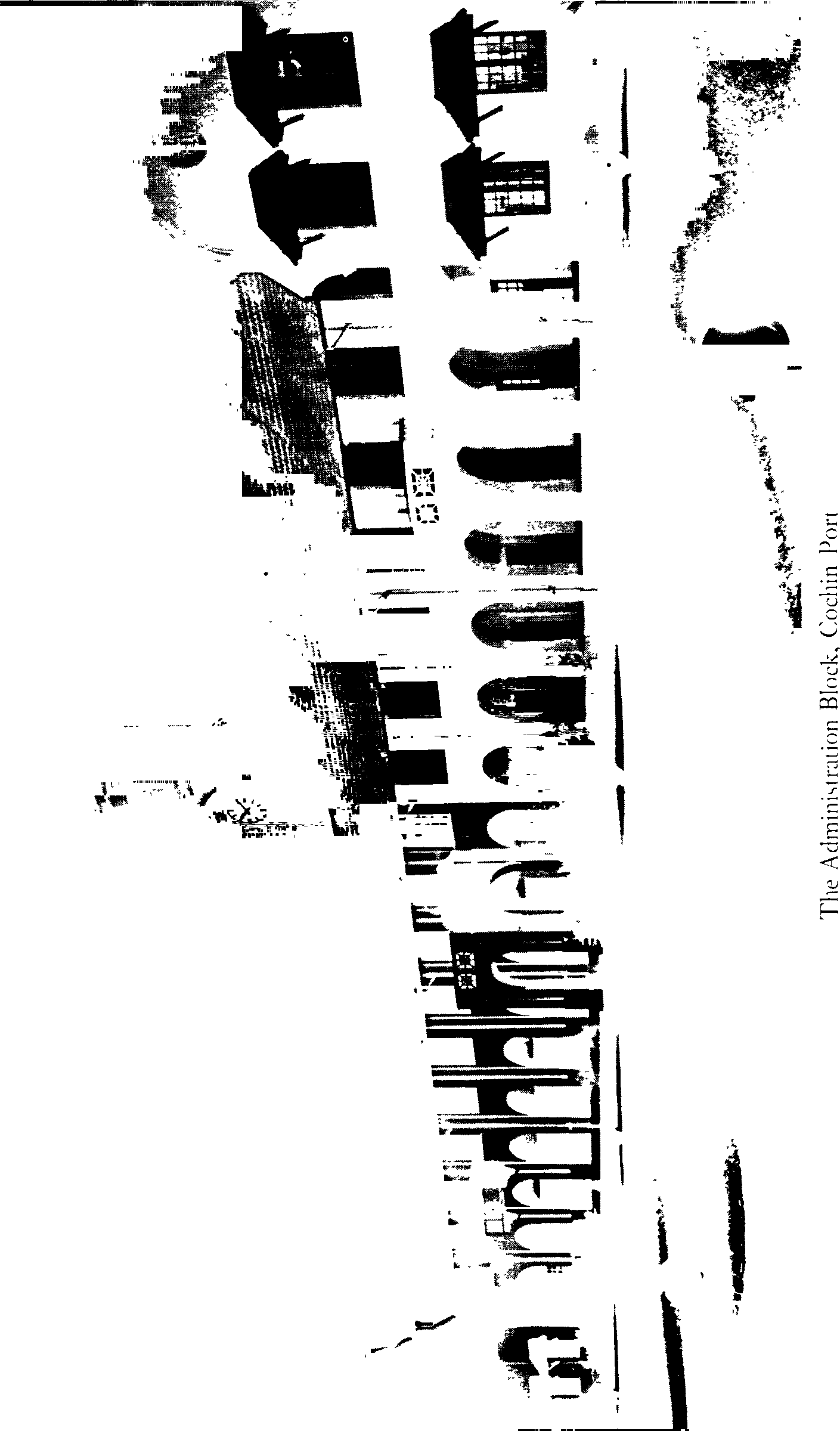

The Administration Block, Cochin Port

Hillingdon Island and Cochin harbour in •v4i hoto-

graphed from a model

Cochin harbour’s memorial plaque

Bird’s-eye view of Hillingdon Island from the top of the

8O

8o 8o

8i

97

iz8

'44

signalstation, looking south . - *4i Sir Robert and Lady Bristow . . i9z Some of the men who built Cochin harbour . ip3, zo8, zoo

LIST OF MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

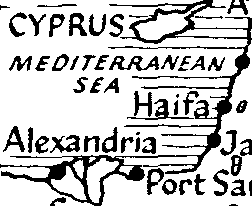

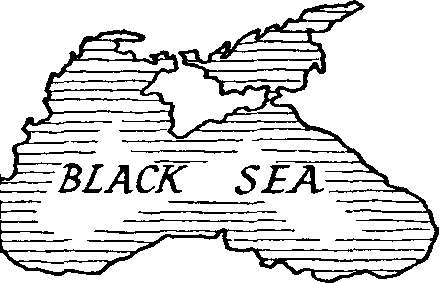

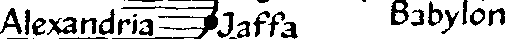

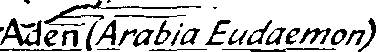

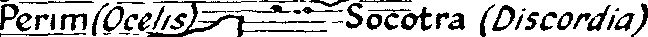

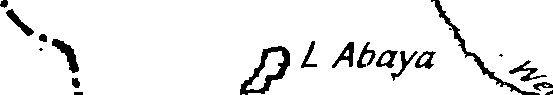

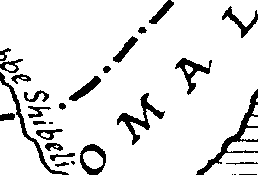

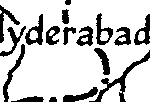

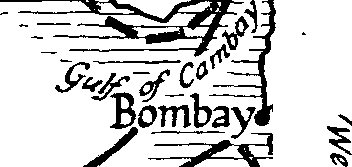

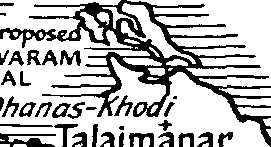

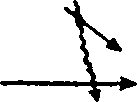

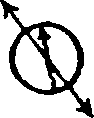

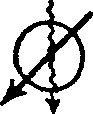

The inland ports in the middle east The early sea routes to India South India

The inland ports in the middle east The early sea routes to India South India

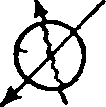

Cochin and backwaters

Cochin and backwaters

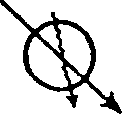

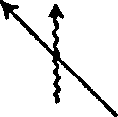

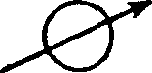

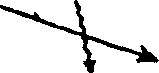

Diagram of winds and currents . If2

I NTR ODU CTI ON

N Writing this book the Author seeks to realize and present four main objectives in their proper sequence. Part One deals chiefly with history as such. It describes the function of inland ports (caravanserais) and their gradual replacement by sea-ports and roadsteads. It traces in broad outline the ancient road and sea routes from the Middle to the Far East. Politically it shows how the alternating accessions to supremacy by European nations dis- places previous powers in their influence abroad and also affects the fortunes of those countries with whom the previous powers had formerly traded. Incidentally, it reveals in each case how the influence of rival religions can affect political, cultural, and econo-

N Writing this book the Author seeks to realize and present four main objectives in their proper sequence. Part One deals chiefly with history as such. It describes the function of inland ports (caravanserais) and their gradual replacement by sea-ports and roadsteads. It traces in broad outline the ancient road and sea routes from the Middle to the Far East. Politically it shows how the alternating accessions to supremacy by European nations dis- places previous powers in their influence abroad and also affects the fortunes of those countries with whom the previous powers had formerly traded. Incidentally, it reveals in each case how the influence of rival religions can affect political, cultural, and econo-

mic developments.

As a typical example of these several aspects the Author has selected the history of the Port of Cochin, where he spent the last twenty-one years of his Government service. Cochin is the chief centre of Malabar and South Indian commerce, but originally, and within the same area of the sheltered lagoons or backwaters which characterize the coastline of what was once, and is now again, Kerala, lay the port of Muziris—the first and chief emporium of India, according to ancient writers. It was situated at the mouth of the Periyar River about eighteen miles north of Cochin, but at a date as yet unknown for certain the impetus of heavy inland floods burst through the low-lying foreshore or shallow bar at Cochin, and so provided a larger and better centre for larger and better

ships. This date is traditionally recorded as A.D. *34• but the Author thinks the slow formation and deepening of the Cochin entrance may have been in progress for centuries before then, and that the culminating ‘push’ may well have been in i i4*

In order to complete the quasi-historical part of his book the

INTRODUCTION

The second main objective is described in the Author’s ‘Per- sonal Narrative’ which forms the substance of Part Two. This objective is concerned first with the solution of four difficult groups of problems comprised equally under the heads of Ad- ministration, Finance, Commerce, and Harbour Engineering. Not the least of his difficulties lay in the fact that the principal officers concerned in the administration of Cochin at Government levels were being constantly changed, so that after twenty-one years there had been sixty of them altogether: sixteen Ministers, four- teen Chief Departmental Secretaries, ten District Collectors, ten Political Residents, and ten Diwans, that is Chief Ministers of Indian States. In addition, the Author served during the terms of five Viceroys, five Presidency Governors, five Commanders-in- Chief of the Indian Army, five directors of the Royal Indian Navy, and all the Civil and Military Air Authorities. Finally, there were four successive Maharajahs in Cochin and Travancore States over the same period. The Author’s work brought him into some degree of direct responsibility and relationship with nearly all these dignitaries.

The second objective in Part Two is to reveal the vast differ- ence which lies between the purely objective history of these twenty-one years and a detailed account of them by the person most intimately concerned. And this is not merely a personal matter. All historians know that in arriving at the facts of long ago it is of the utmost value if a private letter, or a diary, or even a household account-book can be found which indirectly provides the very clue for which they have been seeking.

Thus the ten chapters of Part Two give the unquestionable details for the earlier part of what is written in Chapter Six of Part One.

The third main objective is contained in Part Three. This objec- tive is again subdivided. First, it describes, in as much detail as may be permitted at this time, the immense difficulties between four Governments and between the Author and commercial repre- sentatives, which all had to be surmounted before his proposals and designs for the transformation of the newly formed deep- water harbour into a major pon of India could be started and finished. Secondly, there are introduced certain short glimpses of his home life, social duties, diet, and household expenditure, also of his servants and their tendencies in one way or another. These

XC1

INTRODUCTION

The last object of Part Three is to relate the coming of the War early in September ip3p and to show how the Port had been just ready to meet the long-expected denouement both in equipment and administrative machinery. For many reasons the various dis- cussions and happenings of the period September ip3p to March

*94• have not been included. Many are still secret; of some it is inadvisable to speak, and all are redundant to the first three main objectives of the book, which ends dramatically enough on the coming of the War and the successful completion of all that the Author had conceived in ipzo and his Staff had set themselves to

accomplish.

The fourth main objective, however, contained in the Epilogue (Part Four), is not wholly irrelevant; it reveals first the political and economic situation in India as it was soon after the War started, and second, the highest form of Hindu religion as it was then in the mind of one of the greatest Indian writers, Sri Auro- bindo, who was living in South India, though the Author was not acquainted with him personally. His outstanding work the Life Divine maintains a level of scholarship with a fluency of style and a continuity of logical sequence over i ,*•7 pages which, in the Author’s opinion, is a rare literary achievement. This book, with more daring than discretion, perhaps, the Author has attempted to review in the short compass of five thousand words. Finally, the Epilogue fitly closes with a brief account of what has happened in Cochin since i s4

not a 'professor’ of history. His method has been, first, to read and compare many histories one with another, second, to extract

I NTRO D UCTI ON

the gist of them, and third, to reinterpret that gist in the light of his professional insight as an expert in harbour design and port administration. It is this methodical process which has enabled him to begin his book with the assertion that ‘The history of civilization is written largely in the history of its ports’. The same principle permits him to ‘jump the queue of history’, so to speak, and pass on to the next phase of port evolution before reconnect- ing the ties between them.

A C KNO WL E D GEMENTS

O

UT Of many hundreds, high and low, whose names I should remem- ber with grateful thanks, I record but a few, from i 8f 8 onwards.

The timely actions of some helped to keep alive the demand for a deep harbour at Cochin, and others, in due time, strove to create it:

Captain Castor, Plaster Attendant, Cochin, i86o. Mr. Sliaughnessy of the P.W.D. $ladraS, • 7°

Mr. Aspinwall of the Cochin Chamber of Commerce, i 88o.

The Madras Government itself in i too.

Sir Charles Innes, K. C.S.I., C.I.E., Collector of Slalabar i 9i i—i 5, and Member of Governor-General’s Council i p• 7-

Messrs. Allan Campbell fi Sneyd of the P.\V.D. Madras. Captain Leverett, Port Officer, Cochin, for over twenty years. The members of the md foe Committee, Cochin, i pzo.

The pioneers of the Harbour Staff, IQ 2O—7'

Messrs. F. G. Dickinson, J. H. Duncan, Sambandam Mudaliyar, Abraham the Surveyor, and Natesan, the General Foreman.

The Madras Government, and especially Sir C. P. Ramaswamy Aiyar, K.C.S.I., K.C.LE. (Law member), Sir George Boag, K. C.I.E., C.S.I., Sir Hopetown Stokes, K.C.S.I., K.C.I.E., Sir Cyril Jones, K.C.I.E., C.S.I., Sir Donald Field (British Resident), Sir Charles Herbert, K.C.I.E., C.S.I. (Diwan of Cochin State and finally British Resident in Hyderabad State), Sir J. B. Brown, K.C.I.E., and Air. E. C. Wood, C.I.E.

The later Harbour Staff (• 9°7 35). Slessrs. A. G. Milne, C.I.E., M.LC.E.,

M.I.M.E. (Acting Harbour Engineer-in-Chief during my absence on

leave and sickness), hlessrs. Bruce and D. Lamont, XLB.E., J. V’hite, Khan Sahib Biccu Balu, C. W. Knight, P.A.S.I., and Slessrs. Venka- tareswaram, Panniker, Punchipekesan, and Venkataraman.

At the Government of India: Sir Zafrula Khan, K.C.S.I., Sir James G rigg, K.C.B., K.C.S.I., Sir H uQh Dow, G. C.I.E., K.C.S.I., Sir Jeremy Rais-

fnan, G.C.I.E., K.C.S.I., Sir T. ViJya Raghava Acharia, K.B.E.

At the Government of Cochin State: H.H. the Maharajah of Cochin, Sir Rama Varma and his Staff, especially Sir Shunmukham Chetty (Diwan following Sir Charles Herbert).

The Port Staff (i 9 jy— i), Captain G. F. Fletcher, Port Ofhcer, and Cap- tain A. Sheppard, Chief Harbour Plaster; the Harbour 5taff as before with Messrs. Bappoo Khan, Fernandez, and K. S. Menon; Mr. M. S,

ACKNOWLED GEMENTS

Menon, Barrister-at-Law(Legal Adviser), and the Rev. G. A. N.Shackle (Defence Assistant).

Mr. A. G. Milne took over from me in i s4• and remained during the War, which in turn brought new and urgent developments of the fourth-stage plans in order to keep pace with the growing requirements.

I deeply regret to record with sorrow the early deaths of four of my most devoted staff, namely:

Mr. John White, Dredging Superintendent and Chief Engineer (pipeline). Khan Sahib Biccu Baloo, Chief Dredging Officer.

Rao Sahib Sambandam Mudaliyar, Senior Staff Ofhcer and Secretary. Mr. Panchipekesan, Officer Manager, Engineering Accounts Section.

Never in my experience did men give harder or better service than these, service which, I fear, must be regarded as the main cause of their sudden and unexpected passing. Their names may well be inscribed in the Cochin Roll of Honour.

I must also record with much gratitude the honorary services of my pre- sent Secretary, Mrs. Dorothy Burrows, who, over a period of ten years, has gladly typed and retyped these chapters during their several reconstructive phases.

Finally, and with feelings I cannot express, I remember the lady who, in

I pz 3, when Lord Willington was troubled with doubts because so many opponents of Cochin were pressing him to abandon the project in favour of another, was providentially given an unexpected opportunity of supplying

private and convincing information which completely reassured him and saved the situation for Cochin. This lady became my wife, and her subsequent part in the affairs of Cochin has been recorded in the Personal Narrative.

R. B.

XV1

PART O NE

A PORT HISTORY OF z,șoo YEARS

B

CHA P T E R O NE

ROMAN AND PRE-RO MAN

Ports and Pirates. Commerce and Culture. fioJcrJ and Peoples

HE history of civilization is written largely in the history of its ports. Before men had learned the art and science of ocean navigation or built their ocean-going ships, many historical caravan routes had been provided with ‘inland ports’ which served not only as resting and reconditioning places for man and beast, but also as junctions with other routes and as exchange marts. These inland ports were the khans and caravan- serais of ancient history, those far-off days when travellers and traders journeyed in convoys across deserts and mountainous wastes for thousands of miles east, chest, north, and south. In these meeting-places travellers living far apart geographically ex- changed ideas and news while the traders sold or exchanged their goods. The elements of a world-wide civilization mere thus born in the ancient inland ports. For example, Petra, in the Trans-

T

Jordan valley, has been indentified as the ancient capital of the Nabataens, a people of old Arabia who occupied the borderland between Syria and Arabia from the River Euphrates to the Red Sea. Petra, as can be seen from its ruins, was a rock centre of culture and religion as well as a trading terminus or junction. Its origin is unknown, and its tombs reflect both Arabian and Graeco- Roman architecture, as well as Egyptian. Reliable authorities consider that evidences of this constructional evolution clearly indicate that Petra had cultural relations with many different groups of people, as might be expected from its position and function as a great trading centre.

The caravan route from China lay roughly along the zone of the 4 ° N para11e1, with arms penetrating southwards, as well as to northern India, and thence to Baghdad and Antioch. The main east-to-west route bifurcated at Marakanda, the northern turn

passing via the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea at its south-eastern extremity. Apart from the above, the most important route east-

COCHIN SAGA

ward ran direct from Petra to Basra (Charax) and farther east- ward to Barbaricon (near Karachi), v•hich was then a port at the delta of the River Indus. A more northern branch bifurcated at Persepolis, passing through Phra to Kabul, where it joined another easterly route to China. There was a short westerly route from Petra leading to a place known as Rhinocolura, west of Gaza, and a more southerly route to one at Gerrha on the Persian Gulf adjacent to the island of Bahrein. Northwards from Petra yet another route led through Busra to Damascus.

The dangers of ocean travel are familiar to all, even now, and must have been far greater for the pioneers, who, venturing forth from the Nile and the Euphrates, slowly evolved from the old river-craft the sea-going galleys and the trading vessels of the Arabians and Phœnicians. But if the sea could bring danger and disaster, the salt deserts and sandy wastes, the rocky ascents and descents, and the treacherous footholds of mountain passes must have presented far greater toil and risk to life and limb for those early traders. Moreover, the roving bandits who haunted the trading routes were a further menace, and, from an economic standpoint, the essential charges of middlemen and the taxes or dues imposed by the rulers of every large or small State through which a caravan might pass, added enormously to the traders’ risks and costs.

Inevitably, therefore, when ocean transport became feasible the development of sea-ports led to the disuse of inland ‘ports’ and caravan routes. The process was slow, but once experience began to manifest the freedom and general superiority of sea travel by a direct route, international commerce gradually adapted itself to the new conditions. As neill be shown in what follows, this process of adaptation was and is still the underlying difficulty of every would-be reformer of world commerce and trade routes.

For example, how far air freighters may replace the mammoth ocean-going freighters of to-morrow, and perhaps demand enormous inland ports as well as sea-ports, remains to be seen; but if this century has taught us anything at all it is that the miracles of to-day are the commonplaces of to-morrow. For example, the growth of world population and the overtaxing of the earth’s soil in the production of food z ill entail the discovery and opening up of nez’ productive areas, and the immense tracts of virgin soil contained within the Amazon Basin and its tribu-

Tt/RKET

Antioch

S

Beirut ”””

Damascus

_ Baghdad

Khi.a. Tashkent

Bukhara

Samarquand

As&ra6ad e ’7

- Teheran "MesheJ

Port Said

-

- Petra

s) AQ 2bñ

”+ I’ EILS fA

8asra

Bundar Abbas

itarachi

— (& b icon

„.„ °e— 6 & A s I & ••s•a• °»c• -

" • Mecca

' ‘ d

JDd“ he

Aliles

— pained cities or sites s.dorvn khos :- {Ger•r.hqs

THE IWLKJ'4D PORTS IM ¥I-IE: MIDDLE EAST

COCHIN SAGA

taries seem to be one of the ‘musts’ of modern life. For this pur- pose many large ‘air-ports’ in jungle clearances will have to precede new sea and river routes.

As we have seen, caravan traders were always subject to robbery and violence, and as seaborne traffic gradually supplanted the older system it was inevitable that piratical vessels should infest the coastwise routes. This applied especially to sea routes between Egypt and India, the offenders being largely Arabs, who, in fact, were probably the earliest navigators in these parts.

Piracy at sea has had different objectives and different classes of promoters. Simple theft and robbery with violence are probably as rîfe to-day as ever before, if not more so. Another form of piracy is that of the privateer at sea, the ‘privateer’ being a vessel under the ægis, if not the direct orders, of a nation whose objec- tive is to seize and plunder an enemy’s merchant ships. A third form was and is that of groups of traders who finance private opposition in order to buy out or destroy legitimate competi- tion.

A study of piracy in all its forms gives a clue to the real purpose and significance of sheltered ’ports’ as distinct from coastal ‘road- steads’. Goods from or to ships lying at a roadstead are usually carried either in craft carrying sail or towed by tugs, except when the sea is too rough and the vessels have to lie idle, sometimes for a week or more. This uncertain timing and the double handling of traffic to and from shore add a fifth form of piracy, that of constant pilfering of goods between ship and shore, a common pest at all roadsteads.

From a purely economic aspect, therefore, it is easy to see the further purpose of sea-ports. Caravan routes were very slow, devious, and dangerous in themselves. As knowledge of naviga- tion increased it was clearly advisable to seek the shortest sea routes to the nearest sea-ports assured of safe harbourage and good trade prospects. This search began to develop rapidly when a strong land power gained control of main sea routes, and, aided by greater wealth and influence, began to build larger ships, yet not so big as to present them carrying their cargoes into river mouths, for example, or close inshore behind projecting head- lands. The next phase began when enterprising shippers or governments discovered that by building moles or breakwaters

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 }OO YEARS

across the foreshores a roadstead could be converted into a har- bour where the amount of present and potential traffic justified the adventure financially and the physical features of the coastline were not unsuitable for such an interference with the normal littoral drifts and currents. Another phase began with the coming of steam in place of sail; and especially with the opening of the Suez Canal in i 86d, when ocean-going traffic from east and west was vastly increased and major port terminals improved quickly both in size and depth of water, also in wharf space and faster handling appliances on shore and ship, thus avoiding the ‘double- handling charges’ between ship and shore and securing the quicker ‘turn round’ of ships in all weathers. Incidentally, the Suez Canal killed the fine old East Indiamen and tea- and o ool- clippers.

In addition, however, sea routes had been so protected, from the time of the Roman Empire onwards, by the supremacy of sea- power that, except for outbreaks when sea-power slowly changed from one state to another and buccaneering became a quasi- political occupation, piracy had largely disappeared except in a few and especially well-hidden places where the risk of discovery was least.

This outline of the history and growth of sea-ports indicates the main functions of ocean terminals, which may be summarized thus: the import and export of raw materials and manufacture, as well as grains, pulses, minerals, and fuel; the provision of facilities for the repair of ships and the supply of ships’ necessities: water, fuel, fresh food, stores, spare parts; any extra needs for naval, military, or air purposes. The essential facilities and equipment required for the making and daily use of sea-ports will be detailed in Part Two.

Sea-ports have thus become specialized in favour of trade and defence rather than culture. The old caravanserais, or inland ports, as we have seen, provided a meeting-place for travellers who exchanged news and views of the arts and cultures of their respective countries. It is an interesting pursuit to trace the early sources from which nations were thus influenced by others, and at a time when broadcasting and television would have been regarded as supernatural.

Experts classify these influences in four groups, a dominant,

7

Suez “'•

’‘G 0 RDAN

* aba

Kerman

r A

/AF-0 I-iANISTAN

Simla

L t. Sinai

Kalat

. DELHf

EGY PT

o Medina Yenbo

,,• • Ftiyad h

Cl\abar • Gwadar

Karachi

.Ahm6abad

cambay

Na yb• da

oMecc “” & & s I A

Broach

Khartoum /

Xasala

YE ME • •

>Sana

•Hodeidah !

i

*Addis Ababa

ibouti

b

Mangal i•e

. Cannanor

”*’''”’ t"

- K E N YA v^

- Y0

EARLY SEA ROUI¥S fO fNDfA

COCHIN SAGA

a strong, a slight, and a probable, or trace.1 Thus, if we begin with China we may have to go back to the later Palæolithic or earlier Neolithic Ages to discover what is called the prelegendary period, and here it is important to notice what is a basic factor of art in all periods of culture. It is this—and here the author speaks his own views—the artist and his subject are largely influenced by the nature of the materials available. In China, for example, the coming of the Bronze Age gave fresh inspiration and impetus to the creative skill of the Stone-Age artist. Likewise the same sub- ject, detailed and clean-cut in a hard and good-wearing stone, would, in a softer or coarser-grained stone, necessitate the omission of the delicate minutiae of the original and stress the broader surfaces of its form and proportion, sometimes with remarkable and proper significance. Indeed, this ‘branch’ of art has persisted, whatever material is used, and taken many new forms to-day, forms which obviously peu ert its original inten- tion.

Following up the original Stone-Age and Shang period of the art of China (6OOŒ—2OOO B.C.), a ’dominant’ strain has persisted from legendary times through the successive periods of the Chou, the Han, the T’ang, the Sung, the Yuan, and the Ming and Ch’ing, but in so doing has influenced or been influenced by other forms of art in every period, thus: the Han period ‘slightly’ by the Scythian and ‘strongly’ by the Buddhist Indian; the T’ang period ‘dominantly’ by the Buddhist Indian, ‘strongly’ by the Hindu Indian, and ‘strongly’ by the Moslem Persian. By this time the T’ang period was passing its own dominant ‘composite’ culture eastward to Taiko and the Para or Tempyo culture which followed, and indeed persisted through the periods of Yuan, Ming, and Ch’ing. The h4ing period receix ed nothing fresh except perhaps a ‘slight’ strain from Moslem Persia, but it is important to note that the Renaissance in Europe, which contri- buted largely to the Baroque period, passed on through the Rococo to the Ch’ing in the eighteenth century A.D. In other words, with the growth of economic relations and better com- munications the ’dominant’ strains in art interfused in more or less degree, and, in some cases, very largely according to the ‘domin- ance’ of the great religions of the world. For example, Buddhist

* In this definition and what follows the Author has been greatly helped by the article ‘Periods in Art’, Encyclopædia BEftaniuca, pp. j22—6. ( I p2p).

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 } OO YEARS

India became as it were a meeting and distributing centre both

east and west.

Buddhist India gave ’dominantly’ to the Hindu India which followed the spread of Buddha’s religion into China, especially during the Han and T’ang periods. It likewise passed into Central Asia, but from this point onwards, that is, about the third century B.C., in the early Gupta period, Hindu art as such, although it passed ‘strongly’ into the Moslem period of the thirteenth century A.D., remained more or less stationary except for various schools or branches, of which the Ral put and the Hoysala were the longest-lived.

It is obvious, therefore, that the ‘dominant’ stem of original Hindu art passed eastward and contributed ‘dominantly’ through- out the ages from Buddhist India onwards. Hindu art as such, though contributing something to the Renaissance, has pene- trated nowhere else since the Moslem occupation, but China, in turn, passed it on to Korea and Japan where it has remained the ’dominant’ strain ever since, though debased perhaps in keeping with the corruption of original Buddhism.

This short outline of the history of the spread of art in India and China makes no pretence of describing the variety, vigour, and imagination manifest in so many forms of Hindu art; and it has to be remembered that India, being Indo-European (Aryan) at first, never became a Hindu nation at one with itself. Rome held the West as a whole, but India was not a whole. Central India, with both coasts, was under the sway of powerful Andhra kings; the north-west was chaotic, for Graeco-Bactrians and pastoral nomads (Sakas) from Central Asia were being driven southwards through Sind regions by the Yue-h-Chi, while Magadha kings ruled the north-east. Three strong Tamil kingdoms occupied the south of the Peninsula. The Indians sent no ships farther west- ward than the Red Sea mouth, letting the Greeks come to them. The moving force from first to last came from the XVest; the little- changing peoples of the East allowed the West to find them out. This commercial trend, as oe have just seen, was similar to that of’ art. Not once until Hindu India became Moslem India did any influence from the East penetrate Hindu art proper, which was rat generic from its beginning and fortified by its strict Hinduism in religion and ’caste’. The art of aboriginal India, parallel with that of Chaldea, passed little into the pre-Buddhist India, which was

COCHIN SAGA

itself a direct debtor to the Hindu parent. The reason is clear, of course, for, being an Indo-European country, it is racially bound up with much of Europe as well as Armenia, Persia, and North Hindustan. Indeed, the oldest civilization in India yet discovered, at Mohenjo Daro on the Indus River, not improbably came from the same source as that of Persia and Chaldea, about the middle of the fourth millennium B.C.

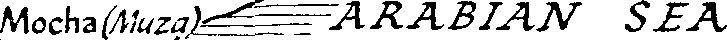

The earliest sea route to India, so far as is known, followed the Red Sea from both arms at its northern extremity, and also from points on the western side connected by road, river, or canal with the delta of the Nile—where Mediterranean traffic from East and West was transhipped. The most important of these points on the Red Sea were: (i) Myos Hormos, near the entrance to the Gulf of Suez; (z) Berenice, just north of the Tropic of Cancer;

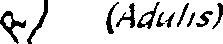

- Adulis, at or near Massawa; (4) Muza, at or near Mocha on the east side; (f) Ocelis, now Perim, or nearby; and (6) Arabia Eudae- mon, now Aden. In addition, the old but smaller port of Ptolemais

occupied the site now called Port Sudan.

This very early Red Sea route then passed round the coastline of southern Arabia and entered the Gulf of Oman, where, at the junction with the Persian Gulf in the Strait of Ormuz, the port of Ormuz, Bandar-Abbas, was connected by road to the direct main route to Baghdad to the westward and also to Kabul to the north- east. Vessels then turned east again and hugged the coast as far as the terminal of Barbaricon, near the mouth of the Indus, where, as mentioned earlier, the major port of Karachi now stands or is close by. At a later stage, larger vessels, after leaving Aden, could either pick up traffic en route or sail direct to the same terminal. This probably occurred after the discovery of the characteristics of the monsoon winds, to be discussed later.

At a still later date, vessels from Aden travelled direct to a port in the Gulf of Cambay called Barygaza, between or near either Cambay or Baroda, but a branch of this same route brought the ships to Jaigarh, now Karjar, on the mainland immediately south-east of Bombay proper. It may be safely assumed that the discovery and use of the regular monsoon winds quickened India’s trade with Europe, but there seems no doubt whatever that before then small Arabian vessels of one kind or another had crept round the coastline for centuries, and that the navigators of

A PORT HISTORY OF 2t j OO YEARS

those early days knew more about the ocean winds and littoral currents than they conveyed to others.

The Roman Empire, as a consolidated whole, politically and economically, may be said to have begun with the election of Cains Augustus as Emperor in the year •7 B.c. He was un- doubtedly a very astute administrator as well as an extremely able

man in the field, and until he died in A.o. •4 gave new life and inspiration to a republic torn almost to pieces by factional strife. It was the Emperor Constantine I, of course, who accepted Christianity. He foresaw the great future which lay before that religion and enlisted its binding power in the service of his

Empire. To this end he presided at the Ecclesiastical Council of Nicaea in A.D. 3z}, but nevertheless organized the agentes in rebus who, ostensibly as inspectors of the Imperial Posting Service, carried on a wide and deep system of State espionage. He was evidently a man with his feet on the soil of the present and his eyes on the spirit of the future, whence came a religion and state- craft, both temporal and eternal in their composition, which has lasted for over sixteen hundred years in Rome, though suffering periodic breakaways by non-Latin countries. The early (and true) Anglican Church, for example, was founded perhaps two centuries before that of Rome under Constantine, and although merged into the Roman ecclesiastical system introduced by Augustine in A.D. 597. broke away again in the early sixteenth

century.

In order to realize the extent of Roman influence east and west during the first three centuries A.D., the following particulars are necessary.

A.D. i q. The Roman Empire included the whole of the coun- tries bordering on the Mediterranean and some others: (modern names) Spain and Portugal, France, Belgium, Holland, Switzer- land, Italy, Sicily, Morocco, Algeria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, in- cluding Albania, Greece, Crete, Turkey, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.

Provinces added A.D. i 8y. Great Britain (excluding a part of Scotland and N. Wales), Poland, Bulgaria, and Rumania. Pro- vinces annexed and abandoned by Trajan A.D. Q8—i i6: Armenia, Mesopotamia, Arabia Petra a, and Assyria.

Thus, the whole of the land and sea-ports in the known West

*3

COCHIN SAGA

were in the grip or under the influence of Rome, and unques- tionably there was a corresponding influence over both Britain and South-west India, for although Rome never ‘ruled’ India, the rapid growth and value of her trade brought new life and vigour to the industries of the East. Moreover, so far as is known, Rome dealt justly and peacefully in a manner not too common in those days. Unfortunately the lure of Eastern products was to prove one of the chief causes of the decline and fall of her early virtues.

4

CHAP TE R TWO

ROMAN AND POST-ROMAN

How Rome found Mn iris, and what it found. How Rome fell and wliy. And what liappened after

EFOnc considering the content and variety of trade which developed between the Roman Empire and India, it may be noted that if India did not seek direct contact with Rome,

B

or rather Puteoli, which was the terminal port for Rome, it is likewise true that Roman ships never passed beyond the tranship- ment port now called Aden, where the Arabian shippers took over the cargoes, while Arabian vessels on their western journeys had to tranship cargoes chiefly at Berenice, Captos, and hlyos Hormos in Egypt. In other words, the big trade links bete een Rome and Southern India were under the control of Rome, and this control included that of the links by road or canal proceeding southward from Alexandria to ports in the Red Sea or eastward to the Persian Gulf. However, it appears that ships of the Roman Navy guarded the Red Sea and its eastern approaches against pirates, and Roman vessels probably plied between Puteoli and Alexandria.

lt may be noted also that the great expansion of Roman trade followed upon the discovery by Hippalos of the secret of the monsoon winds. The date of this discovery has been put at 43 B.c. or A.D. 4i , or even later, the historians dilfering. One certain fact emerges, namely, that Rome without her compact

and contiguous Empire, and without the discovery of the in- variable habits of the two monsoons, south-west and north-east, and their timings and force, and without the great advances made by the Phœnicians in the science of shipbuilding, could not have used her vast wealth and power to promote and expand commerce between India and Europe or to encourage the exchange of know- ledge and culture which slowly evolved.

It is clear also that somè individuel Romans came by sea to India, and individual Indians to Rome, but not primarily for

COCHIN SAGA

trading purposes. The traders belonged to another class. It is also fairly certain that in so doing individual Indians from Muziris made contact with resident Greeks in Rome. After Alexander the Great’s arrival in Northern India many Greeks remained and influenced later the ‘dominant’ type of Hindu art, while other Greeks, returning to the east Mediterranean, brought strains of Buddhic—Hindu religion which may have become incorporated in Mithraism before its transmission to Rome in the first century

B.c. by captured Cilician pirates.

There is no record of individual Romans settling in Southern India, nor is there any trace of Roman architecture. It is stated that a small temple was erected at Muziris to the memory of the great first Emperor, Augustus, but there is no sign of it to-day. The first example of town-planning and a massive style of con- struction is that at hlohenjo Daro in the Indus area, which possibly came from Chaldea. It is remarkable in that its thick walls are double, or hollow, and that a thick damp-course, besides giving the usual horizontal protection at floor level, rises vertically between the two walls as well.

Following upon the successful establishment of regular coastal traffic from Aden, the rapid growth of Roman trade with Muziris in the first, second, and third centuries A.D. led to the introduction of a direct route from Aden to Muziris. Possibly, too, greater skill and experience in the craft of sailing and the construction of larger vessels encouraged shippers to use this more southerly course even in the worst of monsoons, especially as the sighting of the Lakadive Islands (some two hundred miles off the mainland) gave them an excellent guide to their destination. The return journey passed south of the Lakadives, after which some of the vessels called first at what is now Socotra (then Discordia Island) and then at other small ports on the Arabian and African coast east of Suez. A further reason for this southern route might be that with the Roman passion for precious ointments and the perfumes of Arabia’, these last small ports yielded further quan- tities of this valuable cargo for stowage on the top rather than beneath the coarser materials below.

âluziris, now known as Cranganur, lies at or near the mouth of the Periyar River some eighteen miles north of what is now Cochin. The famous backwaters, at the turn of the pre-Christian

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 §OO YEARS

era, were still in process of formation and limitation by the gradual advancement of two strips of land, one from the north and one from the south. These strips were formed out of soil brought down by rivers and canals discharging into the back- waters and coming into contact with material driven on-shore by the ocean ground-swell. This swell usually succeeds the rainy and windy period of the monsoons.

The two natural forces thus slowly built a natural sandy break- water to the lagoon system of backwaters, and at a varying distance west of the mainland—as much as three miles or more in the Cochin area. Not only so, but from time immemorial a particular feature of the littoral had played a great part in the commerce of South-west India with Europe. The effluent from the Periyar River and all other minor streams south of it contains a high suspension of lateritic soil, a brick-like material which yields a semi-liquid mud which is carried out to sea and along the coastline according to the resultant direction of tidal flow, littoral drifts, and wind forces. If and where it meets a force coming from the opposite direction it slowly settles down near that place for the time being. This may be called stage one in the mystery of the h(alabar mud-banks.

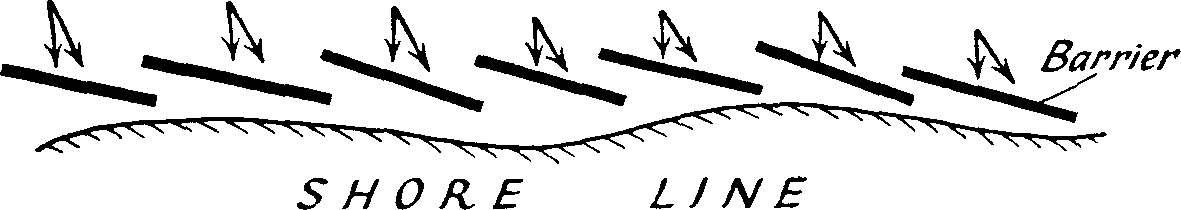

A greater mystery follows. When the south-west monsoon bursts, the seaward edge or ‘toe’ of a mud-bank, lying now on the harder sea bottom at a depth of from three to five fathoms, and at a distance of three to five miles, is stirred up to form a ‘barrier’ and kept in a state of viscous suspension. The unique quality of the mud and its high viscosity in suspension have the effect of tranquillizing ihe whole of the water area over die mud- bank thereby providing a ’natural’ harbour in the sea itself, and cargoes may thus be carried in lighters with perfect safety to or from the beach. Moreover, the rougher the seas are outside the ’barrier’, the calmer becomes the water inside it.

These mud-banks do not always remain in the same place. Sometimes they will move along the coastline in one direction or another; sometimes they are driven inshore and block up the landing-j etties. They are generally situated near a river mouth or where it is known that a river had discharged at one time, but they cannot be regarded as stable. Even when driven rapidly inshore they will disappear completely over a night or two and resume their former or an adjacent position.

C 7

COCHIN SAGA

The unique significance and importance of the mud-banks in relation to the monsoon winds are now apparent. Omitting the traffic from China and the Far East, vessels from Aden could easily choose the best time both for sailing across to Muziris with a good helping wind, from about the end of May, and finding a safe ‘harbour’ off-shore, even in the roughest weather, where they could lie in peace, get rid of their cargo, and take on new loads, and also obtain fresh vegetables, fruits, and water, besides many other amenities of life. A district with eighty inches of rain falling in the months of June to September inclusive, and with a lateritic soil bordering its rivers, which is capable of storing fresh water in its vesicles (approached by wells) is a real haven, especially as a journey of a few miles up one of the rivers will enable fresh flood- water to be taken from the surface even though the heavier tidal salt water flows up or down with the current underneath.

Further, and this is equally important, there were several of these mud-banks along the Malabar coast and southward towards Quilon, so that even if the inner harbour of the Periyar River were temporarily closed there were roadsteads and mud-banks elsewhere serving the same hinterlands. A mud-bank near the Periyar outlet was probably the most reliable, but there were others: (I) near the Beypore River, south of Calicut, at Tundis (or Tundi, or Tyndis, or Tyrtis); (z) at Becare or Porkad, south of what is now Alleppey in Travancore; (3) at Nelcyndra or Nelkunda, not far from Alleppey; (4) at Kolum, near, but north

of, Quilon in Travancore; and others. It is most probable that

these banks and roadsteads changed as the southern of the two outer spits of land growing towards Cochin gave new outlets to sea. Even at this date these spits, in time of heavy floods, are liable to be pierced by temporary discharges in two or three places. At Alleppey itself in monsoon times a subterranean mud stratum will often burst through the comparatively thin layer of sand which covers the sea-bed.

In summing up the position as it was when the direct route was opened to Muziris we have therefore to add the supreme import- ance of three facts: first, the discovery of the law of the monsoons; second, the discovery of the law of the mud-banks (the south- west and north-east winds provided safe passages either way, the mud-banks provided safe and bountiful havens of refuge), and third, the gaining of direct access to the source of luxury products

i8

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 fOO YEARS

to meet the extravagant desires of a mighty and prosperous Empire.

In those days trade was concentrated chiefly at Muziris and Becare. According to the historical evidence the exports brought to these ports from various parts of the hinterland were pepper (‘in great quantities, the pepper of Kottanara’), pearls (‘in great quantities’), ivory, fine silks, spikenards (from the Ganges), betel, diamonds, jacinths; tortoiseshell (from the ’Golden Island’,* and ‘another sort which lie off Limurike’), rice, ghi, oils, honey, cotton, muslins, and sashes. From another source we get the following, and some extras: ‘cinnamon leaf, cinnamon-leaf oil (made from imported raw spice), long pepper, white pepper, black pepper, ginger grass, spikenard-spike, spikenard leaf, amomum, costus, bdellium, pure bactrian; indigo, black; and indigo, prepared after importation, blue.’

In addition, however, Rome bought imports from Arabia and Somali as follows: ‘Frankincense (by way of the Gebbanite Arabs), myrrh (of four varieties), ladanum’; these were all native products, but acting as intermediaries, Arabia also sent to Rome ‘ginger, cardamum, cinnamon flower-juice, Syrian conacum [?], serichatum, ginger grass. And from Somali: myrrh (two varieties), frankincense (three qualities), Hammoniaca lacrima [*], and, as intermediaries, ginger, xylocinnamon, casia (three qualities), cinnamon oil.’

Mr. Warmington 2 gives many other details of the varieties and prices of all these articles as well as of those imports from places within the Empire itself, and adds this comment:

The first thing which strikes us after a comparison of the groups in this list is the much smaller price generally paid for plant-pro- ducts obtained from plants growing ipirfiio the Empire than the price paid to Oriental races outside the Empire. The ‘imperial’ products had no frontier dues, no foreign exactions, and no heavy carriage expenses such as contributed to raise the price of external commodities; they had to bear merely the costs of Medi- terranean travel and custom dues ivirâiii the Empire.

' Vide Commerce l›etu'een the Roman Empire and India, E. H. Warmington.

COCHIN SAGA

Mr. Warrington’s information as to goods and prices from India is taken largely from Pliny, and he makes this further, and significant, comment:

One other important thing is revealed by this group of the list gleaned from Pliny, and that is that the discovery of the monsoons undoubtedly did cause a drop in the prices paid for those Indian commodities that came to the West by sea.

XVithout wishing in the least to undervalue Mr. Warmington’s book, it is pertinent perhaps to mention that recorded history often overlooks points clear to experts in other affairs. In this case the presence of the unique ‘Malabar mud-banks’ and their guarantee of safe harbourage over two hundred miles of coastline were equally if not more important.

Consequent upon these large imports of oriental luxuries Mr.

5Varmington has this revealing passage:

The discovery of the full use of the monsoons brought an im- mense increase in Indian commerce generally, and in Roman im- portation of Indian goods, which stimulated a yet further demand in oriental articles of luxury. Nero’s court set an example, especi- ally during the ascendancy of Poppaea Sabina, who, together with Otho, must have taught Nero many secrets in the art of luxury.

Pliny, in referring to the enormous quantity of oriental spices used at her death, takes occasion to complain of the large amount of specie drained annually by the East from the Empire. Nero himself was accustomed to adorn shoes, beds, chambers, and so on with oriental pearls; most of his palace was decked out with gems, mother-of-pearl, and ivory; and he distributed precious stones among the people. The richer classes, in general, showed a similar prodigality; Otho deliberately invited Nero to his house in order to show him that he v•as not surpassed by the Roman Emperor in the use of fragrant essences which he (Otho) caused to flow like water from gold and silver pipes, a system introduced by Nero into his own palace.... But we must look ahead to Elagabalus (A.D. 218) before we can find a man who wore gar- ments wholly made from silk and took baths in Indian spikenard.

A further passage, taken from Seneca, yields this summary:

20

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 } OO YEARS

He complains about the use of most costly tortoiseshell, tables and precious woods bought at huge prices; crystal and agate vessels, pearls of enormous value lavishly displayed, and ex- tremely costly clothes of silk.... The whole is, in effect a de- nunciation, as we shall see, of costly display of Indian and Chinese luxuries, though the wealthy Seneca himself possessed five hun- dred tables embellished with ivory legs.

Petronius also speaks, but more playfully, of the same faults in women as a whole, who, having been content with ornaments of glass or paste and the like at the beginning of the first century, had in a generation or two discarded their ‘imitations’ for the real stones of India. In other cases, the fashionable courtesans of Rome came to demand jewels, rare essences, and ointments as the price of their profession—a touching sidelight, perhaps, on the action of the Magdalene in giving up her most costly possession as an act of repentance.

Rome could not repay India in goods alone, and great sums of money had to be given to stem the adverse balance. ‘Periplus’ mentions the following exports from Rome:

Great quantities of specie; gold stone, chrysolite, small assort- ment of plain cloth, flow ered robes, stibium, pigment for the eyes, coral, white glass [? 8fica], copper or brass, tin, lead, wine, but not much; sandarach (sindura), arsenic (orpiment), yellow sul- phuret [sic] of arsenic, corn, but only for the ship’s company.

We might perhaps deduce from this list that apart from ‘great quantities of specie’, which in these days would be the trading equivalent of American dollars and British sterling, Rome ex- ported to India materials previously used for clothing before silks became the fashion, and also imports from parts of the Empire for which there was less use than before. Probably they too had the problem of maintaining old industries by exporting larger quantities of what had previously been produced for home con- sumption only.

A list of the Roman coins found in various parts of India, and their dates, give evidence of the rapid increase in the export of coinage which followed upon the ‘discovery of the monsoon’ and the profligate waste of money upon luxuries, as such. Pepper, spices, and other condiments were greatly prized, one would

2 1

COCHIN SAGA

think, as incomparable digestives during the gastronomical per- formances of Roman stomachs in those days. For many they are so to-day.

ft is interesting to note the similarities in weights and measures as used by the Romans compared with those still in force by shippers to-day. The unit of freight was the talent or amphora. An amphora was the Greek name for a two-handled vase or jar used both by Romans and Greeks. The talent was the Greek name for an ancient weight and meant originally a weight to lift or bear. This weight was equal to fifty-seven pounds avoirdupois, or roughly half a hundredweight, and therefore, presumably, indicated an ordinary lift for man-handling. It will be noted too that fifty-seven pounds is about one fortieth of our ton, and even more significantly, it is exacily the average weight ofone cubic foot of olive oil. True, it is also the weight of a cubic foot of proof alcohol, but the likely commodity, certainly from the Phœnician age onwards, would unquestionably have been that of olive oil.

Except for special cargoes (heavy metals etc.), the unit of space on vessels to-day is one ship’s ton equals forty cubic feet of space

—representing the average weight of a mixed cargo. This equals fifty-six lbs per cubic foot and we may therefore assume that one old-style ’lift’ equals, say, fifty-seven pounds; forty lifts equals 2,z8o pounds, and one such ton equals approximately one run, an old name for a large cask holding anything from about zi6 to z}z gallons, one ton of fresh water equalling zz4 gallons, or 2,•4O pounds.

Finally we arrive at the root of all, namely, forty ‘lifts’ will fil1 one good cask of olive oil, a cask not too large or heavy to be rolled over a firm surface and then lifted by a pair of shear-legs on board a ship, if so desired, after filling. The Greeks were a wonderful people for getting to the root of things and dealing in practical realities.

The larger vessels used by the Romans carried up to ten thousand talents, or nearly enough two hundred and fifty tons. The smaller vessels used for coastal trade would carry less, of course, perhaps from one hundred and fifty to two hundred tons at most, and draw not more than ten feet fully loaded. It is quite possible that thèse smaller vessels set the pattern for the native craft used for coastal journeys to-day—the mast raking forv*ard,

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 TOO YEARS

gunwales almost awash on a fully loaded vessel, and a cut-throat- looking crew inheriting perhaps many of the hardy charac- teristics of their far-off ancestors.

The history of the ten centuries from about A.D. yoo to i too is so crowded with incident, with shiftings of power and influence, with innumerable revolutions in both Europe and India, that the history of a single port or group of adjacent roadsteads seems at first to be a matter of minor consequence. In seeking a ray of light, a clue in the long succession of causes and effects, one has to return to the time of Constantine I and his action in founding the city of Constantinople in A.D. 3zd as a new ‘Empire’ port and capital, apart from Rome. The necessity for this move had been foreseen by Diocletian forty years previously, and Constantine, recognizing the great economic value of the old port of Byzantium

—founded in about 6i 7 B.c. and partly destroyed in the second century A.D.—resolved to build his new capital on the same site. Byzantium had been the gateway of all sea trafhc passing to and

from the Black Sea to Greece, the Mediterranean, and to the Red Sea, through Alexandria.

It was Constantine I who added temporal power to that of his Christian authority; and how far that double responsibility could be upheld in lands as yet unconverted and unwilling to change, and to what extent Rome sought to enforce that authority are, or might be, relevant factors in the slow decline in Roman influence and prestige which followed. For instance, under the heading of ’Syriac Literature’, the Encyclopedia Britannica records:

The adoption of Christianity by Constantine as the official reli- gion of the Roman Empire had an unfortunate effect on the posi- tion of the Christians in Persia. They were natumlly suspected of sympathizing with the Roman enemies rather than their own Per- sian rulers. Accordingly, when Sapor H (3• 37s) declared war on Rome about 337 there ensued a somewhat violent persecution of the Persian Christians, which continued in varying degrees for

about forty years ... and later persecutions of the same kind.

Nevertheless, it is possible that Constantine deliberately chose to keep Rome as his religious centre while founding Constan- tinople as (so to speak) his temporal headquarters.

The next epochal change in the balance of power followed

°3

COCHIN SAGA

quickly upon the rise of Islamism following the death of Muham- mad in the seventh century A.D. The new religion, aggressively held and implemented by its first adherents, spread with rapidity and violence in the Levant, and among the nomadic tribes. The Moors of North Africa o’ere not slow in carrying their campaign into Spain, o‘here they remained until the fall of Granada in the late fifteenth century. The religious wars between Christians and Saracens further complicated the whole pattern of the Near East, politically and economically. Meanwhile Genoa and Venice were fast becoming, after the eighth century, strong rivals of Con- stantinople’s influence, and could they have been united between themselves might have either succeeded or reinforced the Roman Empire to such a degree as to further its power for an indefinite period.

Especially was this possible during the reign of Charlemagne,

v ho, in the mind of ordinary men, was regarded as the great champion of Christianity against the creed of Islamism. He was canonized in the year i •*4. though much of his history is legen- dary rather than factual. But whereas Venice was united and

strong, Genoa was politically crippled by internal dissensions between nobles and commoners. All five powers, moreover— those of Rome and Constantinople, the Arabs, Venetians, and Genoese—and of course the Greeks, not to mention others, v ere deeply at cross purposes in seeking help and arms from other states, and the whole picture is one of savage competition, intrigue, and war.

Venice, on the final downfall of the later Roman Empire in the twelfth century, was left as the best-organized and most in- fluential body to take over the commerce of Rome with India, but instead of sending ships of her own to Aden was content to employ all the intermediate shipping and land agents and confine her own direct activities to the Mediterranean area. Most of these other agents were Arabian, who during this period extended their influence by reinforcing in what is now Calicut a certain tribe as local residents, especially occupied in foreign trade. These were called the hlappilahs, or Moplahs, and though many had been in Calicut before the Mohammedan era, all embraced with fanatic zeal the religion of Islam and its Prophet. In fact, much of what Rome had lost passed into the hands of Eastern rulers and traders rather than of Venice.

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 f OO YEARS

The history of South India during this same period is likewise one of conflicting states, large and small, many, in fact, being districts rather than states. There is no doubt whatever that so long as Muziris remained a strong national emporium, and Rome united many states if not in friendship at least in a strong common interest, South India was relatively at peace. Muziris, however, partly due to the decline of Roman commerce, but also very probably because the Periyar river port was becoming less reliable owing to the gradual formation of the Cochin outlet by natural means—and the alteration in the balance of tidal forces within the delta—had lost its supreme importance. It is quite possible also that the old merchants at Muziris, especially Jews and Christians, read the signs of the times and shifted to Cochin as soon as the new outlet became more or less stable; but to what extent the trade of Muziris fell off then, or was transferred to Calicut or Cochin, we have as yet no certain information.

South India had likewise become a political battlefield during this long period, and although the records are confused, and it becomes difficult to trace a design or pattern in any of the opera- tions, there can be no doubt that the germ of war for the sake of gaining new territory was epidemic and virulent, as it was in Europe. All this has been recorded as fully as is necessary or reasonably possible by Mr. K. M. Pannikar in the opening chapter of his book Malabar and the Portuguese, and need not be retold here.

5Vhat was happening in Europe and South India was but one example of the convulsions o hich raged not only in the Mediter- ranean countries but also in Britain, after the departure of the Romans. This long upheaval in temporal affairs, however, may well have soo•n the seeds of a great reformation in thought and culture which came to full growth in the fifteenth century—the Renaissance. For Britain this slow growth undoubtedly started in

the reign of Alfred the Great ( 7• oi), the finest of all British kings. The pure ‘Spirit of England’, now deeply under a cloud, was born in the person of Alfred—the spirit of justice and wisdom, freedom and discipline, wide scholarship and culture; of Christian fortitude and gallant knightliness: the herald of a civilization yet to be achieved.

Similar ’choice lights’ of their several nations and generations burned during the next five hundred years, too numerous to

2 }

COCHIN SAGA

mention for the purposes of this book; but the course of religion and commerce pursued their disputive ways notwithstanding. Some authorities put the date of the Renaissance as corresponding with the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in the year •4f i , but this is acknowledged to be a coincidence rather than a cause.

The Renaissance was born of the suffering of men in all countries, a people not broken, nor even despairing, when the successive phases of the Black Death in i 34 and after threatened to extinguish the race of man altogether.

Nevertheless, many of the old ports survived, and the old middlemen who served them. The oldest sea adventurers of Arabia had regained their prestige and increased their influence in South India, Egypt, and North Africa. Muziris had shifted itself some eighteen miles south to Cochin and all was as it was before Rome came on the scene, except that Venice had succeeded her, and, farther to the c est, a nation which had then a flowering of adventurous spirits and bold navigators conceived a new plan for the capture of East and Far East trade which was to have revolu- tionary consequences. Incidentally it was during this long interval that the south-west coast of India acquired new status by the adoption of its ‘Malayalam Era’. ThiS occurred in A.D. 8zf, not improbably when the last Hindu monarch to uphold a united Kerala, or his immediate successor, relinquished his overlordship. Thus, when India, apart from Pakistan, became one in A.D. Ip47

the h(alayalam equivalent was M.E. 1122.

2ñ

CHA PTE R TH REE

THE PORTUGUESE IN INDIA

Influence of Politics

ORTUGw in the fifteenth century, as a State apart from the parent country, Spain, was little more than four centuries old.

P

Spain of course dates from remote antiquity, with caves of the Palæolithic period, caves which also exist in the part now called Portugal; and its history of warring tribes of invaders from the earliest Greek times, of Phœnician traders and their influence from 1600 B.C. onwards, Of Moorish invaders and Jewish settle- ments, of its religion and culture, weaves a many-coloured pattern of time and change.

It is not improbable, and an interesting hypothesis, that the early settlers, in Spain, generally referred to as Iberians, spread from the east coast to the west and mixed with the Phœnicians who traded at all Mediterranean ports, and some beyond. Portugal could have provided either a terminal or the point of departure to Britain for Phœnician trading, and the evidence of Iberian origin still exists in the form of skulls, stature, and other features among the small and dark Welsh, Irish, and Highlanders, and in northern parts of Cornwall and Devon.

<7

COCHIN SAGA

writer, and with all this, a genial man of wide experience and culture.

Thus, the rise and fall of Portuguese influence in Malabar or

Kerala forms an instructive chapter of history. It was made pos- sible because of the remarkable example of Prince Henry the

one of the founders of, a chair of theology as well as of medicine and mathematics in Lisbon. He invoked the aid of Arabs and Jews and a Majorcan Master Mariner in the making of sea-charts and instruments, and he was a research worker of acute perception himself. His range of sea and land exploration extended round the v estern coast of Africa from about 3 y° N to the Equator, and v herever he v ent he sought to civilize and improve.

His work in the Azores and Madeira brought the islanders much agricultural help and progress in their ecologic conditions. Moreover he had the personality which inspires others to follow a lead, and gave an example and impetus to Portuguese adventure which was to last for a century after his death, extending perhaps also to England, Spain, and Holland. He had the bold spirit by which great things are wrought, combined with the gifts of con- structive foresight and the courage that endures. If Portugal could have produced another such Henry at the right time, the history of the Portuguese in Malabar and the Far East, and the resulting history of the eastem ports, might have been more per- manently affected. The impetus and all-round ability of Henry naturally inspired Portugal, but few realized that, with rare exceptions, it is only the exceptional man of many parts who can bring lasting reforms to a country.

There were, however, other factors in the causal background v-hich cannot be overlooked. The spirit of the Portuguese was still inflamed with the military and religious ardour which had inspired the Crusaders and the Knights Templars, the Portuguese branch of which had been reformed in the previous century. Moreover, thirty-five years after the death of Henry the Naviga- tor, Manoel I undoubtedly had some very capable men about him. The names of Bartholomeu Diaz, Albuquerque, Almeida, and Pacheco are well known as worthy followers of Prince Henry.

z8

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 TOO YEARS

Diaz rounded the Cape in •4 and reached a point off what is now Durban in latitude 3z{° S. His ships were two, one of only fifty tons and one smaller still. His ship’s log, if he kept one, must have provided interesting reading. Incidentally, he named the Cape of Good Hope Cabo Tormentoso no doubt for very good reasons. Fourteen years later he and his ship, and several others, foundered in a violent storm off Brazil—towards which coast equatorial currents and trade winds had driven them.

So it was that, concurrently with the loss of Bartholomeu Diaz, King Manoel chose the adventurous mariner Vasco da Gama to lead the next expedition to India, a man born in the year of Henry the Navigator’s death. He was said to be a resolute and resourceful seaman, but it seems that he had little culture and no previous conception of the situation as he was to find it. So far as is known, moreover, he had none of the wise and constructive statesmanship of Henry the Navigator, no knowledge at all of Oriental psycho- logy nor of the power of Islam influence which had developed in India, and especially at Calicut. He was essentially a capable master mariner of single mind and purpose: bold, brave, ruthless, and arbitrary. We may well imagine the consequences of such a man with three tiny vessels, the largest of two hundred tons, and one hundred and seventy men all told, setting out to displace an age-old Arabian monopoly in India, especially if part of his intent or instruction was to impose the rulership of Portugal over Western India, or part of it. Confronting him, on the other hand, was an Indian culture and religion twice as old as that of Portugal, and a particularly violent and inherently bloody-minded sect of Arab traders, the Moplahs. As recently as ip2I this same sect rose over an imagined grievance and committed acts of the most revolting cruelty.

Vasco da Gama bears a bad name in India. He is also charged, and perhaps rightly, with equally revolting cruelty. In his case, certainly, the evil he did has lived after him, and not the good. But in the sober judgement of time there are many other aspects to be considered. First, it was a cruel and bloody age of torture, poison, and murder throughout the world; an eye for an eye was the standard of justice, bloody war the only arbitrator, incon- ceivable massacre of innocents the outcome. What Vasco is alleged to have done is but a speck on the full page of the history of inhuman cruelty.

COCHIN SAGA

Has India forgotten what she suffered under Timur’s invasion in i 3p8, and the Mogul Dynasty of • f • 5 : Babur’s massacre of Hindus, and Akbar’s first seven years of rule after i }6, years of continuous bloody wars? Has England forgotten her Wars of the Roses, and the judicial murders which followed, the burning of witches and heretics later still* Have Christians forgotten the

Inquisition, or Moslems the savage murder of unbelievers* In- deed, it is open to some doubt if Vasco really began the assassina- tion. The crime of Vasco which chiefly condemns him is unique in the West. It, or something equally sickening, is certainly not unique in the East.

Let us now review the position as Vasco found it, but first the conditions of his voyage. Vasco’s flagship, and one like it, the Sc. Raphael were square-rigged and of shallow draft ‘because of the reported banks and shallows off the African coast’. They had ‘castles’ fore and aft, and mounted twenty guns, some of them breachloaders. The sterns were square, the stems carved to repre- sent their respective patron saints. ‘The crews wore either full armour or leather jerkins and breastplates, and carried crossbows, axes, and pikes’—it may be hoped only when in battle. But, even so, and in that climate, one can only marvel at their hardihood and endurance. The third ship was the Berrio a small ship, a lateen-rigged caravel, fitted out as a store-ship. Her role was to be that of loading water and stores somewhere off the west coast of Africa in readiness for Vasco’s return, but by the time Vasco arrived all but three of the crew were dead, and one of these died in a passion of gladness and excitement on seeing his master and shipmates again.

During that long period of waiting, Vasco had reached Calicut on 2oth May •4v , and left about the end of August, that is after the worst of the south-west monsoon was over. The return to Lisbon occupied another year, and the whole expedition lasted a little more than two years. In those days ships from wine- producing areas drank less fresh water; men preferred the wine to

which they were accustomed, red or white. The hot and very

humid climate of Malabar, and life on board a ship at anchor, with

crowded small spaces in which to live, comprise about the worst

conditions in which anyone can drink great quantities of which were stored Lisbon.

red wine, in particular, on board before leaving

A PORT HISTORY OF 2 $OO YEARS

Vasco da Gama’s character, if strong, was undoubtedly tem- peramental. He has been variously described as firm and patient, proud and irascible, authoritative and obstinate, brave and violent, and it is easy for Europeans who have lived in Malabar to under- stand how such a man, under great physical and mental stress, could be all these things in turn, and especially if he wore armour or a leather jerkin, and drank copious draughts of red wine.

Let us now turn to the rate helm. The power of Islam was then nearing its dominance in North India and over all the trading routes between Europe and India. In fact the Mogul Dynasty, as such, was founded in North India only twenty-seven to thirty years later. Who then, were these armed interlopers with the hated red Sign of the Cross on their ships’ sails? Were they not the same people as those who were turning the Moors out of Spain and elsewhere* And what did they herald now? More propaganda, more violence and robbery?

One can imagine the excited chatter of the bazaars, the mid- night talks of the merchants, and the political discussions else- where. A direct sailing from Calicut to Lisbon would clearly sidetrack the whole of the ancient trading route; and all the links in the chain of profit, from the owners of the coastwise sailing- craft to the rulers of Persia or Arabia or Egypt (all of whom col- lected dues on imported or even ’through’ traffic), would be broken, those of traders and middlemen as much as any. As it happened, there was no particular bond of union between the Moslem who traded and the Hindu ’Samuri’ (or Samorin, or Zamorin) who ruled Calicut, and provided the ruler could have made a good bargain with Vasco he would probably have been glad enough to do so. Arab pressure, however, proved too strong for him, and although Vasco probably took away sufficient evidence of good trading possibilities and a great deal of other information, the voyage had been otherwise indeterminate and unprofitable. There is a legend that before going back Vasco called at Cochin, but it lacks verification.

Portugal also reacted very quickly, but differently, on Vasco’s

return, and in March of the following year King Manoel sent out a fleet of thirteen vessels under Captain General Cabral. On this occasion the leader sailed with twelve hundred soldiers and sailors and seventeen ecclesiastics, of whom eight were Franciscan monks who were to be left in India, and would appear to have been

COCHIN SAGA

ignorant of the fact that Syrian Christianity had been introduced and practised in South India a thousand years before. The fleet ran too far south and afterwards encountered such bad weather as to lose four ships in a great storm and three more at other times. It was in one of these that the gallant Bartholomeu Diaz perished, but Cabral had another navigator with him in Nicolas Coelho, a man who had been with Vasco in his recent journey. Coelho took a course to Mozambique and then to Melinda, where he picked up two Indian pilots who knew the sailing route across the Arabian Sea to Calicut.