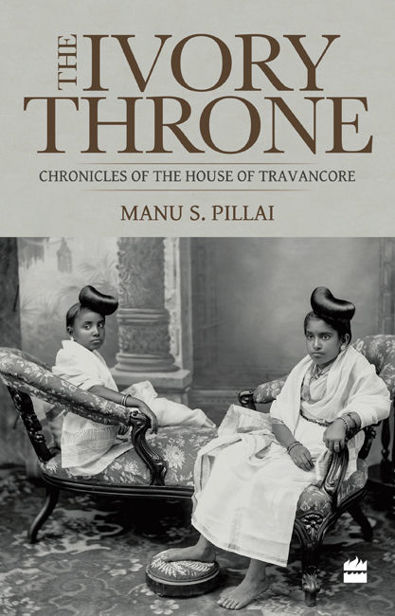

Ivory Throne

Table of Contents

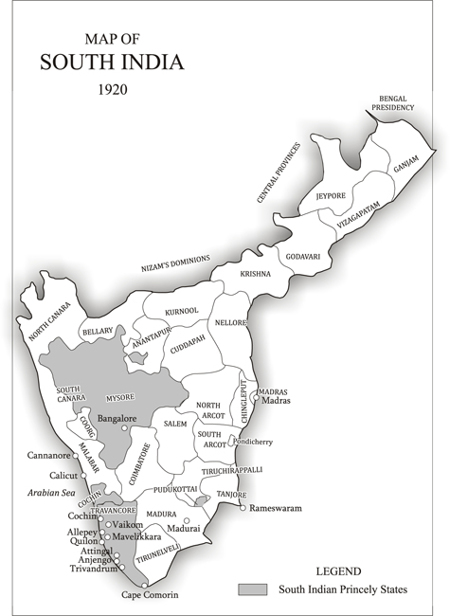

Introduction: The Story of Kerala

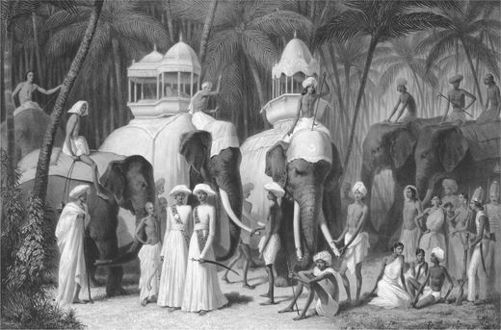

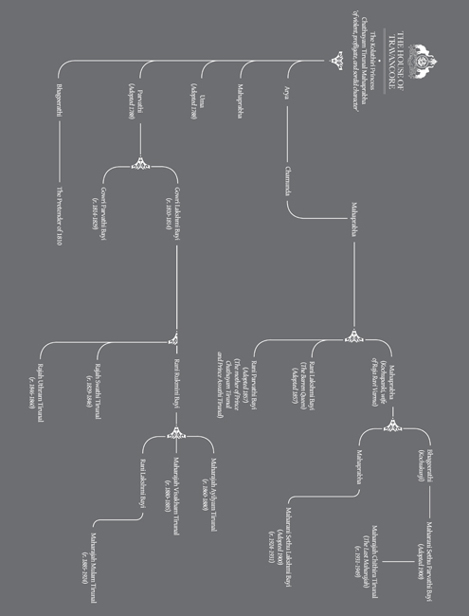

Éléphants du Radja de Travancor (Elephants of the Rajah of Travancore) (1848), lithograph by L.H. de Rudder based on a drawing by Prince Aleksandr Mikhailovich Saltuikov.

Chronicles of the House of Travancore

MANU S. PILLAI

HarperCollins Publishers India

Introduction: The Story of Kerala

Introduction: The Story of Kerala

I

n July 1497 when Vasco da Gama set sail for India, King Manuel of Portugal assorted a distinctly expendable crew of convicts and criminals to go with him. After all, the prospects of this voyage succeeding were rather slender considering that no European had ever advanced beyond Africa’s Cape of Good Hope before, let alone reached the fabled spice gardens of India. Da Gama’s mirthless quest was essentially to navigate uncharted, perilous waters, and so it seemed wiser to invest in men whose chances in life were not especially more inspiring than in death. Driven by formidable ambition and undaunted spirit, it took da Gama ten whole months, full of dangerous adventures and gripping episodes, to finally hit India’s shores. It was the dawn of a great new epoch in human history and this pioneer knew he was standing at the very brink of greatness. Prudence and experience, however, dictated that in an unknown land it was probably wiser not to enter all at once. So one of his motley crew was selected to swim ashore and sense the mood of the ‘natives’ there before the captain could make his triumphant, choreographed entrance. And thus, ironically, the first modern European to sail all the way from the West and to set foot on Indian soil was a petty criminal from the gutters of Lisbon.1

For centuries Europe had been barred direct access to the prosperous East, first politically when international trade fell into Arab hands in the third century after Christ, and then when the emergence of Islam erected a religious obstacle in the seventh. Fruitless wars and bloodshed followed, but not since the heyday of the Greeks and Romans had the West enjoyed steady contact with India. Spices and other oriental produce regularly reached the hungry capitals of Europe, but so much was the distance, cultural and geographic, that Asia became a sumptuous cocktail of myth and legend in Western imagination. It was generally accepted with the most solemn conviction, for instance, that the biblical Garden of Eden was located in the East and that there thrived all sorts of absurdly exotic creatures like unicorns, men with dogs’ heads, and supernatural races called ‘The Apple Smellers’. Palaces of gold sparkled in the bright sun, while precious gems were believed to casually float about India’s serene rivers. Spotting phoenixes, talking serpents, and other fascinating creatures was a mundane, everyday affair here, according to even the most serious authorities on the subject. But perhaps the most inviting of all these splendid tales was that lost somewhere in India was an ancient nation of Christians ruled by a sovereign whose name, it was confidently proclaimed, was Prester John.2

It was long believed that there lived in Asia a prestre (priest) called John who, through an eternal fountain of youth, had become the immortal emperor of many mystical lands. Some accounts said he was a descendant of one of the three Magi who visited the infant Jesus, while a more inventive version placed him as foster-father to the terrible Genghis Khan. Either way, Prester John was rumoured to possess infinite riches, including a fabulous mirror that reflected the entire world, and a tremendous emerald table to entertain thirty thousand select guests. Great sensation erupted across Europe in AD 1165, in fact, when a mysterious letter purportedly from the Prester himself appeared suddenly in Rome. In this he elaborately gloated about commanding the loyalties of ‘horned men, one-eyed men, men with eyes back and front, centaurs, fauns, satyrs, pygmies, giants, cyclops’ and so on. After vacillating for twelve years, Pope Alexander III finally couriered a reply, but neither the messenger nor this letter were ever seen again.3 Luckily for Europe, the travels of Marco Polo in the thirteenth century and of Niccolo di Conti in the fifteenth painted a rather more rational picture of Asia on the whole, but they were still convinced of the presence of lost Christians there, egged on by religious fervour and the commercial incentives of breaching the monopolised spice trade.

If da Gama and his men, weighed down by centuries of collective European curiosity and imagination, anticipated the legendary Prester as they stepped on to the shores of Kerala in India, they were somewhat disappointed. For when envoys of the local king arrived, they came bearing summons from Manavikrama, a Hindu Rajah famed across the trading world as the Zamorin of Calicut.4 This prince was the proud lord of one of the greatest ports in the world and a cornerstone of international trade; even goods from the Far East were shipped to Calicut first before the Arabs transported them out to Persia and Europe. Until the Ming emperors elected to isolate themselves from the world, huge Chinese junks used to visit Calicut regularly; between 1405 and 1430 alone, for instance, the famed Admiral Zheng He called here no less than seven times with up to 250 ships manned by 28,000 soldiers.5 In fact, even after the final departure of the Chinese, there remained for some time in Calicut a half-Malayali, half-Chinese and Malay community called Chinna Kribala, with one of its star sailors a pirate called Chinali.6 The city itself was an archetype of commercial prosperity and medieval prominence; it hosted merchants and goods from every worthy trading nation in its lively bazaars, its people were thriving and rich, and its ruler potent enough to preserve his sovereignty from more powerful forces on the Indian peninsula.

Da Gama and his men received one courtesy audience from the Zamorin and they were greatly impressed by the assured opulence of his court. But when they requested an official business discussion, they were informed of the local custom of furnishing presents to the ruler first. Da Gama confidently produced ‘twelve pieces of striped cloth, four scarlet hoods, six hats, four strings of coral, a case of six wash-hand basins, a case of sugar, two casks of oil, and two of honey’ for submission, only to be jeered into shame. For Manavikrama’s men burst out laughing, pointing out that even the poorest Arab merchants knew that nothing less than pure gold was admissible at court. Da Gama tried to make up for the embarrassment by projecting himself as an ambassador and not a mere merchant, but the Zamorin’s aides were not convinced. They bluntly told him that if the King of Portugal could afford only third-rate trinkets as presents, the mighty Zamorin had no interest whatever in initiating any diplomatic dealings on a basis of equality with him.7 Manavikrama, it was obvious, could not care less about an obscure King Manuel in an even more obscure kingdom called Portugal, and with a pompous flourish of royal hauteur, he brushed aside da Gama’s lofty ambassadorial claims.

The Zamorin was not unreasonable, however. He clarified that the Portuguese were welcome to trade like ordinary merchants in the bazaar if they so desired, even if no special treatment was forthcoming. Da Gama, though livid at his less-than-charming reception, had no option but to comply, having come all the way and being too hopelessly outnumbered to make a military statement to the contrary. And so his men set up shop in Calicut, under the watchful eyes of the Arabs, peddling goods they had brought from Europe; goods, they quickly realised, nobody really wanted here in the East. The hostility of the Arabs did not help either; for they, recognising a threat to their commercial preponderance, initiated a policy of slander, painting him and his men as loathsome, untrustworthy pirates. When complaints about this were made to the Zamorin, they were met with yawning disdain, not least because the Portuguese had precious little to contribute to business or to the royal coffers. The first European trade mission, thus, was a resounding flop as far as the Indians were concerned, and when da Gama’s fleet departed Calicut three months later, they left behind a distinctly unflattering impression on the locals.8

In Europe, however, the expedition was received as a great success, as it had finally broken the thousand-year Arab monopoly, and also because the few goods da Gama had successfully bartered in Calicut fetched sixty times their price in Western markets. In March 1500, therefore, King Manuel assembled a second armada to go to India. This time they were better prepared and more confident, led by the redoubtable Pedro Alvarez Cabral. It also helped that by the time they arrived in Calicut, the forbidding Manavikrama had died and a younger, more amenable prince was parked on the throne. The Portuguese got off to a more promising start, as a result. But their enthusiasm waned when they realised that demand for European goods continued to be feeble at best. In the spice auctions too, wealthy Arabs consistently outbid them and Cabral’s ships were not filling up as expected. As the weeks passed he began to grow impatient and belligerent. The policy of defamation unleashed by the Arabs incensed him, and he suspected they were colluding with local suppliers to prevent the sale of spices to the Portuguese. At one point, then, Cabral sacked an Arab vessel, provoking retaliation from Muslim merchants who burned down his warehouse and killed between fifty and seventy Portuguese men. Cabral took to the safety of the sea and looted every ship he could find and, in what was meant as a lesson to the Zamorin, bombarded Calicut from afar for an entire day, killing nearly 600 people.

Cabral had realised by now that there was no way he could trade in this city so long as the Arabs held sway. He decided, in what was a calculated move, therefore, to sail south into an alternative harbour and try his luck there. During his months in Kerala, he had learnt a fair deal about regional politics and identified a very useful chink in the Zamorin’s armour. And this was the port of Cochin in the south, held by a Rajah called Unni Goda Varma. This prince was a dynastic descendant of the Chera kings of yore and possessed a pedigree and caste superior to that of the haughty Zamorin. Yet he had been enslaved by Calicut: he had to pay tribute; all his pepper had to be submitted to his overlord; he was not allowed to mint currency; and perhaps most humiliatingly, the scion of the Cheras was prohibited from tiling the roof of his own palace, forced to thatch it instead, like the hut of a common peasant.9 Cochin resented this debasing treatment imposed by the Zamorin and so, when Cabral’s ships appeared by his shores, the Rajah received them with open arms, magnanimously granting several trade privileges and much pepper. He hoped, as Cabral knew and exploited, that with the aid of the Portuguese, he would finally be able to throw off Calicut’s yoke and regain his independence and dignity.

It was a fateful juncture in the history of Kerala. Essentially, at this moment, Cabral had declared war between Portugal and Calicut, and Unni Goda Varma had rebelled against his feudal master after generations of servitude. The Zamorin, when he heard of these proceedings, was furious. He resolved not only to cut down the arrogant foreigners, whose only advantage was a superiority of arms and better navigational skill, but also to punish his audacious tributary. An enormous army started southwards while a massive fleet of eighty ships sailed out of Calicut to confront the Portuguese. Unni Goda Varma, incidentally, was prepared for a showdown and began to gear up for war. Cabral, however, knew that for all his bravado and grandstanding, the Portuguese were no match for the Zamorin and would only be utterly routed if they engaged in a full-fledged military conflict. To the great chagrin and disappointment of his new ally, then, Cabral had the lights of all his ships put out and in the dead of the night slunk out of the harbour and sailed off to Portugal, leaving a trembling and perfectly betrayed Unni Goda Varma to the mercies of an incandescent Zamorin.

For quite some time the Portuguese repeated this exercise of harassing Calicut from a distance, sailing out to Cochin to load their ships, and then fleeing the moment the Zamorin’s forces arrived to face them. In 1502, for instance, da Gama himself returned and irrevocably upped the ante by not only looting Arab ships in the vicinity of Calicut, but also sinking a vessel full of pilgrims returning from Mecca, including women and children. He instigated the Kolathiri Rajah of Cannanore, another resentful foe of the Zamorin,10 to open hostilities and then demanded that every one of the 5,000 families of Arabs in Calicut be expelled and the Portuguese be awarded an absolute monopoly over the spice trade. In another merciless episode, da Gama captured and sacked twenty-four ships headed for Calicut, and then set them as well as the 800 crew inside on fire. To add insult to the injury, an exalted envoy was tortured and returned with dogs’ ears sewn on his head, with a note suggesting that perhaps the Zamorin should ‘have a curry made’ of the burning human flesh.11 As usual, the moment 50,000 soldiers marched into Cochin, the Portuguese set sail, abandoning Unni Goda Varma once again to his own feeble defences.12 The Rajah, as it happened, had to flee with his life and seek refuge inside a temple sanctuary this time.

For the many years after this, the Zamorin was engaged in an uneasy tango with the Portuguese, on land and at sea. Trade, in the meantime, suffered as the latter initiated a policy of blatant terrorism in the Indian Ocean, with the Arabs unable to hold their own against these aggressions. In 1508, then, the Zamorin in alliance with the Sultan of Egypt and the Ottoman Turks inflicted defeat on the Portuguese, only to have the favour returned in 1510 when the latter invaded Calicut itself and set the royal palace on fire. When such multinational partnerships failed, some decades later the Zamorin forged an alliance with the Adil Shah of Bijapur and the Nizam Shah of Ahmednagar, and together they battled the Portuguese in 1571. The Zamorin, as his part of the joint offensive, seized their fort at Chaliyam and ‘demolished it entirely, leaving not one stone upon another’, according to a contemporary account.13 But, as usual, the enemy was quick to recover, and this costly sequence of sanguinary war and desultory peace cascaded into the seventeenth century as well.

It was only after the arrival of other Europeans in India that the Zamorin was finally able to expel the Portuguese from Kerala. In 1663, in alliance with the Dutch, he mounted his strongest campaign ever and together they conquered Cochin. But if anyone expected an era of peace to follow, it was rendered only a daydream. For the Dutch smoothly slid into the political vacuum left by the retreat of the Portuguese and, to the abiding resentment of Calicut, assumed the mantle of protecting the Rajah of Cochin. They even went out proactively to interfere in regional affairs, instigating a rebellion here or settling a succession dispute there, and otherwise undermined the Zamorin’s power. This, in fact, was a deliberate strategy on their part, for they wanted the Kerala princes and chieftains to remain forever embroiled in petty warfare, which produced ample opportunities for the sale of the by now prized European weapons in return for pepper and other spices, not to speak of widening Dutch influence on the coast.14 This would only be possible so long as there was no dominant authority in Kerala and so one by one they signed independent treaties with even the smallest princelings and chieftains, all at the expense of an increasingly exhausted Zamorin.15

By the end of the seventeenth century, Calicut’s pre-eminence in Kerala lay in complete shambles and the Zamorin’s influence was at its lowest ebb. As the traveller Jacobus Visscher noted, his splendour had been ‘considerably diminished’ by war and it was ‘quite a fiction’ to claim he was the leader of all Kerala now.16 The Kolathiri Rajah in Cannanore, who ruled over the northern extremity of the coast, was now completely independent; in central Kerala the Rajah of Cochin remained safe under Dutch assurances; and further south, whatever distant standing the Zamorin commanded came to naught.17 These territories were further divided under smaller chieftains, and the whole region turned into one messy political scramble, with the Dutch having the last laugh as they walked away with heaps of pepper and money. In earlier days spices produced in the region were by and large channelled to Calicut, and the harbours of the minor Rajahs were only really ports of call for those headed to the Zamorin’s famed capital. Now, however, each of them attempted autonomously to woo anyone who would heed their call to patronise their respective cities, actively instigated by the Dutch. Commerce began to become irregular and less profitable while petty squabbles grew aplenty all across the land.

At the turn of the eighteenth century, Kerala’s last great age before the advent of the colonial era was inching towards a traumatic conclusion. Calicut’s glory, built through a dynamic partnership between its cultivated Hindu princes and spirited Muslim merchants, characterised by an equally sophisticated internationalism, was reduced to a wistful memory. Beleaguered by incessant war and refractory allies, the diminished Zamorins were no longer lords of one of the world’s great free cities; they were fighting now for their very political survival. They were rendered ordinary, like the other parvenu forces thrashing about on the coast. In the face of determined hostility from European powers that demanded unfair privileges and discriminatory concessions, striking at the very roots of the free trade that had brought prosperity to Kerala, the Zamorins floundered and fell. They did, however, fight valiantly for many long years, and as late as 1607, after a century of battling the Portuguese, the traveller Pyrard de Laval was still able to write:

There is no place in all India where contentment is more universal than at Calicut, both on account of the fertility and beauty of the country and of the intercourse with the men of all religions who live there in free exercise of their own religion. It is the busiest and most full of all traffic and commerce in the whole of India; it has merchants from all parts of the world, and of all nations and religions, by reason of the liberty and security accorded to them there.18

But despite their best efforts, Manavikrama’s heirs were destined to fail. The eighteenth century revealed a Kerala that was only a shadow of its former greatness, a civilization devastated by internal tumult and external assault. It would never regain its former stature in the world, and another brutal century would pass before even a semblance of peace was restored in the region. And this was achieved not through the wise endeavours of its quarrelling princes, but by the superior forces of powers foreign to the land. Marching in by land and from sea, they would brush aside the wreckage of the past and painfully initiate Kerala into the modern age, defining the land as we see it today.

Nestled between the mighty mountains of the Western Ghats and the sparkling waters of the Arabian Sea, exposure to the wider world is an ancient feature of Kerala’s heritage. Since biblical times men came in search of this land, enriching it with wealth, fame and culture. The Babylonians and Assyrians traded here in the centuries before Christ, and the edicts of the celebrated Emperor Asoka name the Keralaputras as an independent country in south India in his day, corresponding with ‘the Celobotras of Pliny, the Keprobotras of Periplus, [and] the Kerobotras of Ptolemy’.19 In the early years of the Common Era this narrow seaboard was a renowned cosmopolitan centre, where men of every country and race were welcomed with open arms. After the destruction of their second Temple in AD 70, Jews escaping persecution in Jerusalem sought refuge in Kerala where they lived in prosperity until the Portuguese arrived 1,500 years later to harass them afresh. Islam too found a home here, not by means of the sword but through the peaceful embassies of commerce. Indeed, such was the level of free multiculturalism at one time that the Zamorin even decreed that every fisherman in his realm should bring up one son as a Muslim so as to become a merchant and sail in the Eastern seas.20 Kerala flourished as an exceptional realm of liberty, peace and plenty, reputed as a haven for one and all.

It is no wonder, then, that the Portuguese were drawn to Kerala. But what set them apart from other merchants was that they came in search not only of spices but also of Christians. The aim, dramatically enough, was to reunite with lost Christians in the East and retake Jerusalem after an ultimate confrontation with Islam. This religious zeal was a legacy of the violent Crusades that had tormented Europe for generations, and there was a rather fundamentalist spark motivating this higher purpose of the explorers.21 And indeed when they reached Calicut, they were thrilled not so much by the magnificent commerce they witnessed there, but by the happy intelligence that resident on this sliver of the Indian coast was an ancient community of indigenous Christians. The old tales that had exhilarated Europe for centuries were finally confirmed and it was with great eagerness that the early Portuguese went out to meet their Indian brethren. But if they expected the Christians of Kerala to revel in joy at being united with them and pledge unconditional loyalty, they were somewhat disappointed. For the Malayali Christians responded with polite bewilderment and courtly indifference, rendering the Portuguese disheartened first and then positively enraged.22

Keen as the Portuguese were to impart their religious wisdom and light in the East, Christianity had in fact arrived in Kerala as early as AD 52, when St Thomas the Apostle (‘Doubting Thomas’) is believed to have set foot on the shores of Cranganore near Calicut. He traversed the region, winning over substantial sections of people with the intellectual and religious merits of his faith. He established seven churches in Kerala, and over time a proud Christian community evolved in the region. Like the Arabs, they were masters of business and emerged as a premier entrepreneurial class, even establishing partnerships with the immigrant Jews. They maintained intimate links with Hindu society as well, developing a fascinating syncretism of culture in Kerala. Their churches, for instance, were modelled on Hindu temples and da Gama himself worshipped in a shrine to the goddess Bhagavathi, mistaking it for a chapel to the Madonna. St Thomas is even supposed to have had an intellectual debate on religion with this goddess at the Cranganore Temple. According to legend, the discussion got rather heated and a weary Bhagavathi decided to decamp and go back to rest in her shrine. ‘St Thomas,’ as Francis Day records, ‘not to be out done, rapidly gave chase, and just as Bhagavathi got inside the door post, prevented its closing.’ And there they stood, for a long time, with the goddess barring St Thomas entry, and he refusing to let her shut him out, until the door turned to stone. As the scholar Susan Bayly states, both Bhagavathi and St Thomas are seen in this story as equally divine figures and in the end, even though the Apostle (representing Christianity) did not gain access into the entire shrine (symbolising the Hindu populace), he secured a ‘significant foothold’ in the region.23

Naturally, then, the Christians of Kerala developed a unique personality of their own, quite unlike the version of their faith practised in faraway Europe. Identities were plastic and even Brahmins, who belonged to the highest Hindu echelons, often converted to St Thomas’s religion, seasoning its indigenous flavour. Many Christians served alongside Hindu soldiers in regional militias and at the end of the sixteenth century, for example, the Rajah of Cochin is said to have employed thousands of Christians in his service. In daily life too, Hindus and Christians interacted freely and the former treated them with great honour and respect. One traveller recorded that ‘there is no distinction either in their habits, or in their hair, or in anything else, betwixt the Christians of this diocese and the heathen’ Hindus, and as late as the closing years of the sixteenth century there was tolerance of intermarriage between the communities.24 In the Krishna Temple in Ambalapuzha an image of St Thomas used to be carried in procession alongside those of Hindu divinities on festive occasions. Across the coast there were temples where only oil ‘purified’ by the touch of a Malayali Christian could be used to light lamps and holy fires. There was a fascinating intermingling of faith and culture throughout Kerala, and Christians were integral constituents of this rich social fabric, arguably more cosmopolitan and certainly less fanatic than in contemporary Europe.25

It was hence that neither the Portuguese nor their pontifical enterprise to unite Christians into one integrated bloc against Islam (and Arab competition) evoked any great enthusiasm in Kerala. After all, these Malayalis had been Christian long before Christianity had reached even the outskirts of Europe. They were heirs to a tradition more ancient than the Roman Catholicism of the Portuguese and had never, for instance, even heard of the Pope; when the Portuguese presumed to claim that the Kerala churches ‘belonged’ to the Pope, quick came the retort, ‘Who is the Pope?’26 The Malayali Christians, as it turned out to the great mortification of the Portuguese, adhered not to the Vatican but to the Nestorian Church headed by the Patriarch of Antioch in modern-day Turkey. Their liturgical language, similarly, was not Latin but Syriac, by virtue of which they were known as Syrian Christians. In other words, the celebrated Father of Roman Catholicism held little consequence for them, and besides the common tag of being all ‘Christians’ they could not be more unlike the Portuguese. Thus, the local Christians whom the Europeans ‘rediscovered’ observed a branch of the faith that Roman Catholicism neither approved of nor upheld.27

As was almost habitual with them at the time, when the Portuguese could not find what they sought in the local Christians, they abandoned all fraternal pretensions and went on to diligently persecute the latter. Over the following centuries many were compelled to accept the Catholic faith and denounce the Eastern Orthodox rites of their ancestors. The Portuguese also set out to purge Hindu elements from their rites, and ruthlessly applied themselves to rid local Christianity of what they derided as ‘Pagan’ influences. They may have reconciled to not finding the fabled Prester John and his legendary treasures, but the zealous Portuguese could never come to terms with a flock of ‘corrupted’, non-Catholic Christians. Eventually, a sizeable Catholic following also grew in the region under the Portuguese banner, along with a minor Luso-Indian population. In the years ahead, as more and more European missions reached Kerala, many new brands of the faith found welcome in the land, establishing other churches with their own distinctive features along the coast.

But if the nature of Christianity in Kerala seemed outlandish, what positively befuddled the Europeans were the peculiarities of Hindu society here. While they did not encounter men with dogs’ heads or the so-called ‘Apple Smellers’, they were most astonished by the principal class of ‘Pagans’ in Kerala. The Nairs, as these serpent worshippers were known, were a martial group, and the most exalted of them was none other than the Zamorin himself. And their customs appeared even more bizarre than those of the Christians. Describing the Nairs, the diarist Duarte Barbosa paints a picturesque, typically exoticised summary of their general way of life:

In these kingdoms … there is another sect of people called Nairs, who are the gentry, and have no other duty than to carry on war, and they continually carry their arms with them, which are swords, bows, arrows, bucklers, and lances. They all live with the kings, and some of them with other lords, relations of the king, and lords of the country, and with the salaried governors … And no one can be a Nair if he is not of good lineage. They are very smart men, and much taken up with their nobility. They do not associate with any peasant, and neither eat nor drink except in the houses of other Nairs. These people accompany their lords day and night … These Nairs, besides being all of noble descent, have to be armed as knights by the hand of the King or lord with whom they live, and until they have been so equipped they cannot bear arms or call themselves Nairs … In general when these Nairs are seven years of age they are immediately sent to school to learn all manner of feats of agility and gymnastics for the use of their weapons …These Nairs when they enlist to live with the king, bind themselves and promise to die for him; and they do likewise with any other lord from whom they receive pay. This law is observed by some and not by others; but their obligation constrains them to die at the hands of anyone who should kill the king or their lord; and some of them so observe it so that if in any battle their lord should be killed, they go and put themselves in the midst of the enemies who killed him, even should those be numerous, and he alone by himself dies there; but before falling he does what he can against them; and after that one is dead, another goes to take his place, and then another, so that sometimes ten or twelve Nairs die for their lord.28

Indeed to the first Europeans, Kerala seemed to marinate in blood as Nairs, serving their numerous lords and princes, lived in a state of perpetual warfare and violent enmity; as Galleti would dryly remark, ‘War was in fact the natural state’ here.29 Perhaps the most emblematic of their ingrained will to kill (or to get killed) was the custom of blood feuds known as kudipaka. If a Nair died at the hands of an enemy, the slain warrior’s family vowed not to rest until they had exterminated the killer’s clan, avenging their dead kin. Families in such epic vendettas often prepared doggedly for years before assaulting each other on a chosen date in a great duel or full-fledged battle, witnessed by massive baying crowds.30 Bloodthirsty loyalty of this nature extended to feudal overlords also. In 1502, for example, when the Zamorin’s soldiers killed three princes of Cochin, 200 Nairs serving as the latter’s bodyguard set out to avenge their dead masters’ honour. Their mission was to claim the lives of an equal number of princes from the house of the Zamorin, and it is said to have taken five years before the soldiers of Calicut put the last of these warriors to death, just outside the capital city. Until then, these chavers, as they were called, persevered on, advancing further and further into the Zamorin’s country, acting as a deadly squad of killing machines, cutting down every enemy Nair they encountered.31 ‘Their chief delight,’ Francis Buchanan would write about the Nairs, ‘is in parading up and down fully armed. Each man has a firelock, and at least one sword; but all those who wish to be thought as men of extraordinary courage carry two sabres.’32

If the reckless bravery of the Nairs (sometimes induced by opium33) impressed the Portuguese, what provoked great sensation and even a degree of romanticism were their exotic marriage customs. Indeed, parallels to their way of cohabitation were difficult to find even in other parts of India, leave alone Europe. The Nairs, it so happened, were what we would today define as extremely liberal, and their women had enough personal freedom to scandalise foreign observers. While everywhere else in the familiar world it was ordinary for men to keep numerous wives, here custom granted that privilege to women as well. As Barbosa recorded, ‘the more lovers a woman has, greater is her honour’. And ladies, high and low, vied to collect beaus and husbands with great avidity. Even princesses and queens were not excluded from this inviting polyandrous tradition; to quote Barbosa once again, ‘these [princesses] do not marry, nor have fixed husbands, and are very free and at liberty in doing what they please with themselves’.34 Wave after wave of Europeans was enchanted (and occasionally horrified) by these exotic customs, inspiring James Lawrence, years later, to pen a twelve-volume novel called The Empire of the Nairs: An Utopian Romance. Since this was translated into both French and German, it was presumably received with great interest and is now considered an early feminist work arguing for parity between the genders.35

Women, in general, enjoyed individual personalities and often ran vast estates and even kingdoms on their own. They were normally educated at least to a basic level and very often grew adept in the art of warfare also. One local Rajah in Kerala, for instance, maintained a palace guard of 300 female archers when the Portuguese first met him, much to their astonishment.36 Country bards sang of gallant heroines putting dreadful villains to death with their superior swordsmanship and prowess. In the Muslim royal family of Arakkal, women had equal rights of succession with male members of the house, ruling in their own right. Females of royal blood moved about freely in society, unencumbered by purdah and that severe seclusion that was their fate in other parts of India. They commanded tremendous respect, besides actively participating in affairs that were the strict preserve of men in less-inclusive societies. When the Italian, Pietro Della Valle, visited the court of the Zamorin in 1623, for instance, he observed many ladies in attendance there and two princesses even came up and studied him with a casual, self-assured confidence, as the following description confirms:

Suddenly two girls, about twelve years of age, entered the court. They wore no covering of any kind except a blue cloth about their loins; but their arms, ears, and necks were covered with ornaments of gold and precious stones. Their complexion was swarthy but clear enough; their shape was well proportioned and comely; and their aspect was handsome and well favoured … These two girls were in fact Infantas of the kingdom of Calicut. Upon their entrance all the courtiers paid them great reverence; and Della Valle and his companions rose from their seats, and saluted them … The girls talked together respecting the strangers; and one of them approached Della Valle and touched the sleeve of his coat with her hand, and expressed wonder at his attire. Indeed they were as surprised at the dress of the strangers, as the strangers were at the strange appearance of the girls …. There were higher cloisters round the court filled with women, who had come to behold the strangers. The Queen …stood apart in the most prominent place, with no more clothing than her daughters, but abundantly adorned with jewels.37

Thus, in Kerala women enjoyed a position of singular importance, not least due to its matrilineal system of inheritance, about which more will be said later.38 Even their highly abbreviated sense of dress seemed outrageously uninhibited to the more conservative and culturally judgemental Europeans, for it was unusual for women to cover themselves above the waist. It was as if they all lived in a state of perpetual dishabille but the fact was that being bare-bosomed was considered perfectly respectable. Outsiders did feel this was somehow immoral but as F. Fawcett would opine, ‘Dress is, of course, a conventional affair, and it will be a matter of regret should false ideas of shame supplant those of natural dignity such as one sees expressed in the carriage and bearing of the well-bred Nair lady.’39 In fact, in one instance in the seventeenth century when a local woman appeared before a princess covered in Western style, she was actually punished for doing this. Her breasts were mutilated by royal order, since covering them were ‘a mark of disrespect to the established manners of the country’. The princess too, of course, was unabashedly bare-breasted.40

By the eighteenth century, however, all this was beginning to change. In 1766, Kerala was unexpectedly drenched in war and blood as the dreaded armies of Hyder Ali of Mysore rained death on the Zamorin and his hapless aristocracy. The Muslim king pillaged and plundered, unleashing such formidable chaos that the Zamorin was compelled to send even his own women and children south as broken refugees. As the marauders gained on his ancestral seat in Calicut, Manavikrama’s heir, by his own hand, set fire to the palace where his ancestors once sat in state and lorded over the riches of their trade. And while the last of the great Zamorins of Calicut perished, thus, in inglorious flames, his feudatories and generals fled en masse, abandoning Kerala to the fiery ambitions of its invaders.41 With their exodus, the old ways of life in the region were devastated. Into the 1790s the English East India Company took over the province, and the ancient clans, once active participants in that enthralling theatre of commerce and power, were reduced to mere landlords with hollow, wistful titles. There was now no leader in the northern half of the coast, and all looked south where alone one prince succeeded in withstanding these convulsions of time, carrying his dynasty and house into modernity. As the Zamorins of Calicut faded into oblivion, it was time for the Maharajahs of Travancore to emerge from the shadows.

In 1752, shortly before the last Zamorin was toppled in Calicut, a hitherto forgotten dynasty made a thunderous reappearance upon the political landscape of Kerala. They had a pedigree that matched the Zamorin’s, and at one time it was to their port of Quilon that the world came in avid search of spices and trade. Their Jewish and Christian merchants had dominated commerce for long years until the Arabs combined with Calicut and transformed the rules of the game, leaving Quilon a shadow of its former greatness. In the centuries that followed, the royal family there became so divided and diminished into feuding households, that they were practically nobodies in the larger scheme of things, their land a political backwater. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when the Zamorin was forging grand alliances with Turkey and Egypt, deploying colossal armies in his wars against the Portuguese, here in the south its princes were fighting petty clannish battles with minor militias supplied by petty warlords.42 While Manavikrama sneered at presents Vasco da Gama offered him, the humble ruler in Quilon not only lapped up similar trinkets but also submitted gifts in return to honour the Portuguese.43 The wide disparity in prestige between the Zamorin and these southern princes could not be overstated.

In the early eighteenth century, however, this house, known as Kupaka, was to experience such a wonderful resurgence that all Kerala sat up and took notice. They had carved up the south into small principalities among their various offshoots, with the extreme south in the hands of the Rajah of Travancore. He ruled over a tiny patch of land between Cape Comorin and Trivandrum, hovering at the periphery of Kerala’s dynamics, with a voice so feeble that it was universally neglected. Travancore cut a miserable figure before the remainder of Kerala’s princes; in fact if any of the Kupakas possessed at least a semblance of power, it was the branch in Quilon. Like Cochin, the prince of Travancore was perpetually vassal to one force or another. In the sixteenth century the emperors of Vijayanagar seem to have levied tribute from him, and by the seventeenth it was the Nayaks of Madurai who periodically plundered his lands. The Nawab of Arcot, a representative of the mighty Mughal emperor, followed, adding ignominy to the prince’s unglamorous circumstances by treating him merely as a zamindar (landlord) at his court.44 It was with some surprise, then, that Kerala awoke with a jolt when this house of perennial tributaries produced a valiant prince determined to rewrite history and drive a fear of mortal existence through the heart of the coastal polity, saving his lands from that destructive wave of invasive war that would engulf all else very shortly.

It was a prince of Travancore by the now-hallowed name of Martanda Varma who achieved this dramatic revitalisation of the Kupaka dynasty, resurrecting their former pride and standing. Born in 1706, he was, in the words of a contemporary, a ‘man of great pride, courage, and talents, capable of undertaking grand enterprises’.45 These were desperately desired qualities at the time, for by now his house had hit rock bottom. Respect for royal authority was at a complete discount and it was Nair chieftains who decided all affairs at court. Atop every hillock and across every river ruled a Nair lord, enjoying hereditary sway over his estates and engaged in fickle battles with assorted neighbours.46 But for all their ceaseless infighting, the Nairs were wholly united in the preservation of their mutual interests by keeping the Rajah permanently emasculated. Temples too, controlled by influential Brahmin grandees, existed in imperium in imperio, as states within a state, and together these factions jealously guarded their privileges from any encroachment by the monarch. As one of Martanda Varma’s powerless predecessors lamented bitterly, ‘the nobles only desire that the kings sit on the throne like mute statues and do only what the nobles wish them to do!’47

Martanda Varma, however, was determined to put an end to this, and enthusiastic about employing all varieties of violence and intimidation to achieve his goals. Even before he succeeded to the throne, he was thoroughly despised by the most powerful clique in Travancore. Known as the Ettuveetil Pillamar (Lords of the Eight Houses), these Nairs had for long harassed the royal family and tamed the king into spectacular impotence. They whimsically played one branch of the Kupaka clan against the other, keeping its princes forever at war while reaping all the rewards of the attendant lawlessness. The Rajahs were unable to retaliate, as custom precluded fealty to any one king alone, and the Nairs were free to make or break their promiscuous allegiances as they pleased. Their impunity was also due to the fact that tradition denied Rajahs the power to divest any noble family of its ancestral rights. Martanda Varma, however, had scant respect for such usages. He earned the wrath of the Pillamar in the 1720s by scheming to rein them in with the aid of superior mercenary forces from outside Kerala, demonstrating early on that he was thirsting for a fight. For years, then, legend has it, these nobles hounded and chased him from one place to the next, reducing him into an illustrious fugitive in constant fear of physical liquidation. Meanwhile, he could only bide his time patiently and vow ultimate revenge on his adversaries when his day came.

That day came in 1729. Upon his accession, Martanda Varma, as a confirmed enemy of the aristocracy, sent a chilling message across Kerala, showing himself capable of not only breaching age-old mandates of tradition, but also of exercising ruthless force to satisfy his ambitions. He set an eerie example, for instance, by slaughtering his own cousins in cold blood when they refused to fall in line with him.48 While this was essentially a family affair, it spelled out to one and all that Martanda Varma hadn’t any scruples about breaking rules or committing sin. He had a cold, calculating zeal that sent a shiver down the back of the feudal class. The Pillamar were promptly on their guard, for they had supported these murdered cousins, and it was patent they would be next to confront Martanda Varma’s vendetta. Soon enough, when evidence fell into the Rajah’s hands of a conspiracy at court, he had the Pillamar arrested summarily and presented proof of their perfidy. In what was unprecedented, instead of chastising the nobles by demoting their powers but otherwise leaving them unharmed, Martanda Varma ordered their immediate execution.49 Their properties were attached and their women and children sold into slavery, with not a hint of mercy or sympathy. And thus perished forty-two noble houses of the realm, obliterating internal opposition from the Rajah’s path and ringing the death knell of feudalism in the region.50

Over the next two decades, Martanda Varma unleashed a formidable military campaign in south Kerala. He first went to war against his uncle who ruled Quilon. Having annexed his territories and acquired the old port, he moved to conquer other branches of the Kupaka dynasty. He suffered a number of defeats and reversals and at one point nearly lost everything when rival relations united to destroy him. But then, he recruited a contingent of Tamil mercenaries, and with their aid regained the upper hand, using stratagems of war traditionally never observed in Kerala.51 In 1746, the last of his fierce opponents gave up resistance and fled, paving the way for Martanda Varma to claim unchallenged sovereignty over the now-united Kupaka kingdom. By 1749, he began to muscle into domains of other dynasties as well, beyond the frontiers of the old Kupaka country, reducing them to ashes.52 One clever pretext after another was always tailored to justify these aggressions, and with his growing military clout, few were able to stall his advances. There was no clemency and by 1752 the armies of Travancore were hammering at the trembling gates of Cochin, having taken by force all the lands south, destroying also, in the process, the final vestiges of Dutch influence in Kerala.53

While Martanda Varma was building strong armies and emerging as the new fountain of power along the coast, the proud Zamorin had turned into a forlorn relic of the past. All that was needed to shatter his derelict jigsaw state was a fateful confrontation with the arriviste warrior from the south. In 1762, Travancore’s soldiers, under the united command of a central authority, routed the paralysed jumble of feudal lords and spiritless retainers deployed by the Zamorin, decisively crushing any remaining prestige that ancient dynasty could claim in Kerala. The balance of power firmly tilted south, and it was up to Martanda Varma’s house to guide the future destinies of the land in a changing world. In 1766, when Hyder Ali dispossessed the Zamorin and other northern chieftains forever, it was only Travancore that could withstand his threat, holding its own in the south until the Lion of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, marched in and waged a bloody war in 1789. But he too failed, ultimately, to take Travancore. A terrible heavenly downpour reinforced the bravery of the Nairs (aided by the English East India Company) to destroy the invaders. Martanda Varma’s legacy was destined to survive for many more years.54

Travancore’s unchallenged pre-eminence in Kerala was short-lived, however, as the political winds were blowing in a new, unprecedented direction, mortgaging its destiny to the newest foreign entrants in the subcontinent. The sceptre of colonialism commenced its rise in India, and this foreign power was shortly to dispose of even such tremendous powers as the Mughal emperor and the Marathas, claiming a right of conquest over the entire subcontinent for the first time in history. Martanda Varma apparently recognised this turn of the tide well beforehand. The Zamorins had taken a hostile position against the Portuguese and the Dutch in the name of dynastic gallantry. And they had lost. Discerning a lesson in political pragmatism, Martanda Varma chose, therefore, not to stand in the way of the ascent of the British and sacrifice the conquests of his lifetime at the altar of princely vanity. He satisfied himself instead with the role of a secondary partner to India’s new rulers. On his deathbed in 1758 he issued seven injunctions for political survival to his heirs, the most crucial of which was that ‘the friendship existing between the English East India Company and Travancore should be maintained at any risk, and that full confidence should always be placed in the support and aid of that honourable association’.55 His successors followed this fiat to the letter, making up with loyalty and obedience to their foreign overlords what they often lacked in personality and vigour.

Their people, of course, were rather less well disposed to this colonial marriage of expediency between a monarchy of recent vintage and an empire of foreign origins. As in the rest of the world, the dawn of the nineteenth century witnessed a Kerala at the very cusp of modernity, set to unleash many waves of change and turmoil upon its restless society. The old ways were discarded in favour of new. Victorian morals and views on life were superimposed awkwardly on the ‘heathen’ practices of yore. In the hasty name of ‘progress’, many of those remarkable distinctions that had once set Kerala apart from the rest of India, and indeed the rest of the world, were relinquished. Material prosperity of the classes and, to a lesser extent, the masses, grew. Modern forces were painfully birthing a new people, inching towards a common nationality alongside the remainder of India that was to fulfil its ‘tryst with destiny’ only in 1947. In the interim, rebellions, first violent and armed, then cultural and socio-economic, were provoked, and that strategic relationship advocated by a dying Martanda Varma was more than once challenged. The aspirations of the people were given expression in communal rivalries among themselves first before they integrated against the princely government ruling over them, in effect as a glorified, worshipped, and romanticised local arm of the empire; as a client regime of the British. The fact, it was ultimately realised, was that the fortunes of Kerala’s last prominent princely line were inextricably intertwined in an umbilical bond with the fate of the imperial enterprise in India. So long as the sun did not set on the British Empire, Travancore would endure.

This book is a chronicle of those fascinating times, from the era of Martanda Varma, the masterful warrior king, down to India’s liberation from colonial rule two centuries after his passing. It is the story of those intervening years when the region became a smouldering cauldron of social, political and cultural contestations, which would leave in their wake a new land so different from its incredible ancestor in the era of the Zamorins and the Portuguese. It is the story also of a monarchy that was constantly reconciling its dynastic prerogatives with the demands of its colonial masters, or trying hard to harmonise social forces that slowly drained power from its hands. Martanda Varma’s heirs were enlightened despots, offering their people many material rewards of modernity and standards of living superior to elsewhere in India (with enduring results in present-day Kerala). But these very gifts of noblesse oblige mutated into tools with which the masses would clamour for power and the right to determine their own course devoid of inherited dynastic paternalism. While the Maharajahs began to get comfortable on their thrones and convinced themselves of their own benevolent despotism, the people rose to challenge that entire world and chart a future guided by their collective aspirations alone.

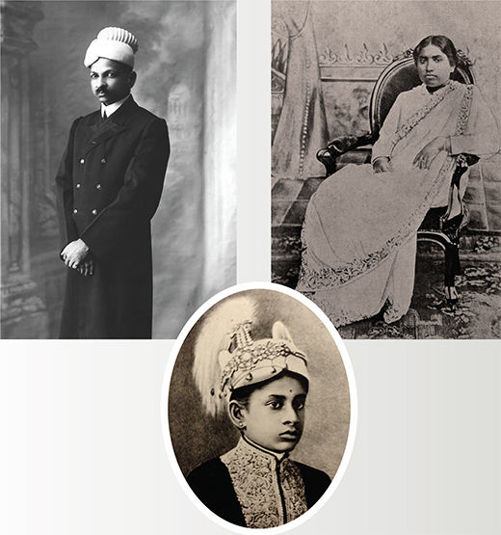

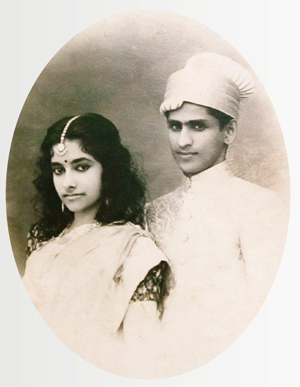

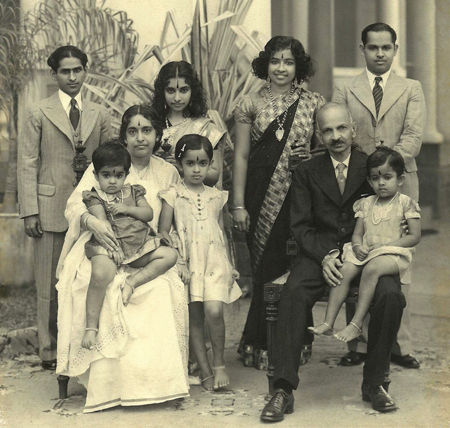

The story of this tremendous transformation is told through the life and times of perhaps one of the most distinguished rulers of Travancore in the modern period. During the 1920s the stormy fortunes of the five million subjects of the state were entrusted into the misleadingly gentle hands of a female monarch, destined to go down in history as the penultimate ruler of Travancore and the last queen of the Kupaka dynasty and its Ivory Throne. She presided over the state during a most critical period, serving her people with considerable ability even as she watched her dynasty suffer inevitable strategic attacks outside while crumbling with dissent within. She occupied a riveting world of court intrigues and illicit conspiracies, hatched not only by scheming politicians beyond the walls of her palace but also by ambitious members of her family in an all-engulfing contest for power. With remarkable stoicism, however, she navigated her troubles—personal, political and dynastic—winning the reverence and love of her people through far-sighted policy and good government. Reigning with much aplomb and majesty on the eve of the dissolution of India’s gilded world of Rajahs and Maharajahs, she earned the unstinting admiration of both the colonial empire that had shaped the country’s past and of nationalists like Gandhi who were moulding its future. And when the final moment of reckoning came in 1947 and Travancore faded before a greater idea of India, she renounced her illustrious (and frequently violent) heritage and effaced herself from the land of her ancestors, as an ultimate romantic emblem of a Kerala that once was. Years later this last heiress of Martanda Varma’s line would die faraway from the kingdom she once ruled, concluding with a tragic dignity a story that had begun generations before.

T

he names in this book follow a certain pattern. For male rulers of the House of Travancore I have used their star-names (tirunals) to avoid confusion. For instance, between 1829 and 1924 all the Maharajahs of Travancore, with one exception, had the personal name, Rama Varma. They are therefore distinguished by their star-names as Swathi Tirunal, Ayilyam Tirunal, Visakham Tirunal, and Mulam Tirunal.

For women, I have retained their personal names in most instances, but wherever confusion is likely to arise, I have relied on nicknames, while full names are given in the endnotes. Thus, for instance, where three women—grandmother, daughter and granddaughter—are all named Mahaprabha, I have retained the proper name for one of them while the others are referred to by their nicknames.

Some titles and names in this book have also been standardised throughout the main text. For instance, the word ‘Maharajah’ alone has variously been spelt in different sources as ‘Maharaja’, ‘Maha Raja’, ‘Maha Rajah’ and so on. So too surnames like ‘Iyer’ have been spelt sometimes as ‘Aiyar’ or ‘Aiyer’. Original versions may be found in the endnotes and the bibliography, but throughout the principal text, I have chosen the ordinarily used version and employed that alone for consistency.

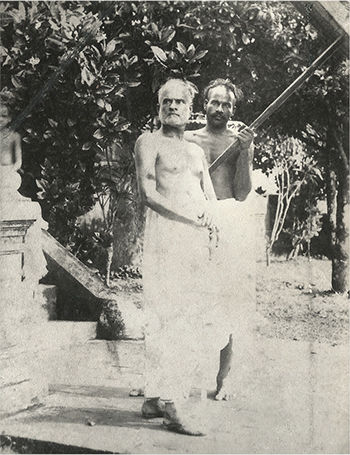

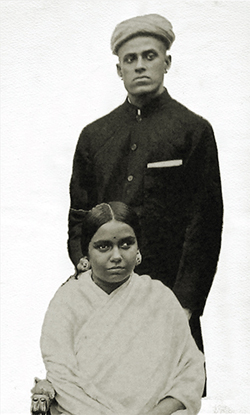

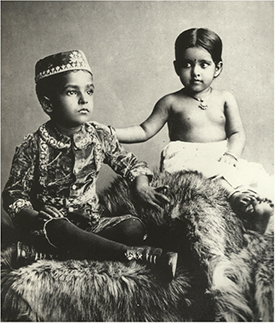

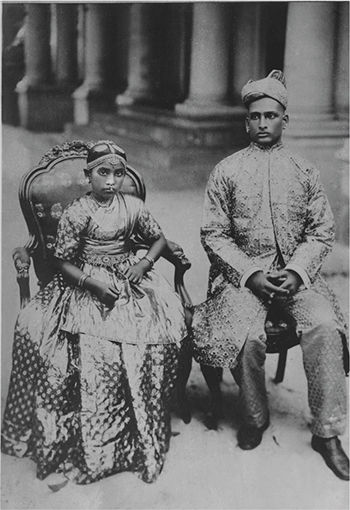

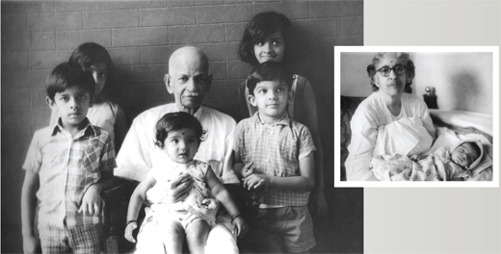

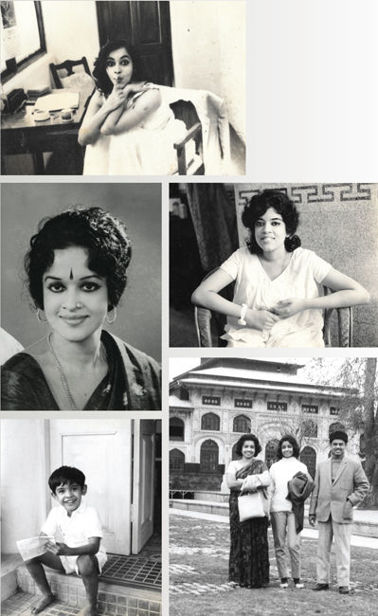

The images in this book, unless specifically mentioned, are either from open resources (such as the paintings by Raja Ravi Varma) or from private collections and the albums of members of the Travancore family.

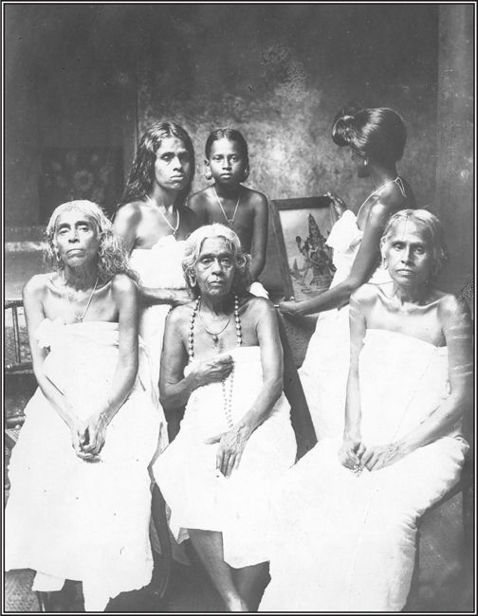

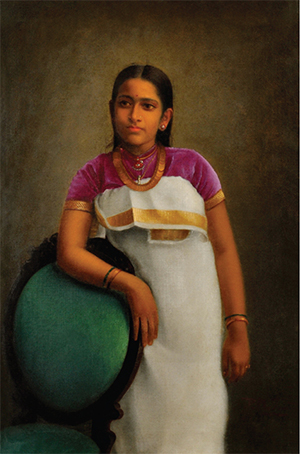

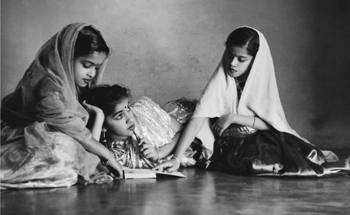

The matriarchs of Mavelikkara

I

n 1862 when Ravi Varma was presented at court to the Maharajah of Travancore, little did he presume he was destined to emerge as one of the great luminaries of his generation. He had arrived in Trivandrum, the principality’s capital, as a physically unprepossessing, swarthy stripling, whose facility and sophistication, however, belied his age. At fourteen, he had, in the manner of the Malayali aristocracy of the day, had an education in Sanskrit and Malayalam, with an honourable appreciation of music, drama and, rather unusually, painting. His family were country aristocrats lording over a few thousand acres of freehold at the grace and favour of the Maharajah, who was closely connected to them by marriage. It was, in fact, the principal occupation of the men of Ravi Varma’s clan to marry princesses of Travancore and to spend the remainder of their days in splendid luxury. But that was if they were fortunate, for the number of princesses unengaged at any time did not always match the hordes of eligible young noblemen in waiting, and more aristocrats were left disappointed than exalted to a life of courtly recreations.

Used as he was to a country setting of fields, temples and rustics, for the young boy Trivandrum was a majestic change. Its architecture, a charming blend of the Kerala and European styles, was vastly different from that of his traditional home in Kilimanoor. There were leafy avenues and well-kept boulevards where the Maharajah went out for his drives, surrounded by public buildings, libraries, schools and all the other accessories of a nascent modern state. There were Englishmen and women, novelties he had never before seen, while at court munificent patronage was extended to some of the best musicians, artists and scholars in southern India. The Maharajah, having taken a liking to the boy from Kilimanoor, gave him leave to stay in the capital under a special sponsorship to study art. Accordingly, the uncle, who had chaperoned him to Trivandrum, installed Ravi Varma at their family’s townhouse and departed, leaving the teenager a responsible master of his own destiny.1

In the palace, young Ravi Varma ‘wandered the halls and corridors, studied the artists paint, observed their paintings, saw colourful processions, and pored over albums of European art, which the Maharajah collected’.2 The royal library and manuscript collection were at his welcome disposal and he read and absorbed with an enthusiastic voracity. He had seen tales from Hindu mythology depicted on the walls of temples and in the murals at his family home, but what he really wanted to do was to bring them to life himself in paint; and specifically in oil paint. At the time, the chief durbar artist was Ramaswami Naicker of Madurai who alone knew how to mix and paint in oil, a technique he jealously guarded from rivals at court. Ravi Varma was no exception and consequently found himself kept at a watchful distance. ‘Despondent,’ one account goes, ‘he marked his time, with none to initiate him into the mysteries of perspective and chiaroscuro, of compositions and complementary colours’ with ‘all the encouragement he received being the occasional advice of the Maharajah that perseverance is the best guru’.3

The young painter seems to have taken this royal counsel, probably given out of impatience than with pregnant meaning, to heart. For by the time he died in 1906 he would become one of colonial India’s great artists, a celebrity whose life the press followed keenly, and whose paintings collectors vied to obtain. With typical panache and style, he would divide his seasons between Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta, Agra and other urban centres of the British Raj, entertained by one fawning patron after another. He was paid not only in money but also with more prestigious gifts of jewels, gold, robes of honour and even elephants. His social circle included Congress leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and Gopal Krishna Gokhale; the crème de la crème of Bengali intelligentsia such as Surendranath Banerjea and the Tagore family; pro-imperialist statesmen like Sir Sheshiah Shastri and Sir T. Madhava Rao; alongside an impressive assortment of opulent Maharajahs and zamindars. Everywhere he always found ‘opened for him the gates to the rich and powerful’, although, ultimately, ‘it was his personal charisma that enabled him to hold on to this milieu’. For he was also by this time ‘a likeable socialite, equal in status to most of his clientele, with a gift for being able to flatter with his art even the least attractive features of his customers’.4

Indeed, Ravi Varma’s success came not only because of his innate talent and hard work, but also because he had the advantage of high birth and social cultivation (not to speak of canny networking skills) that made him seem an exotic catch to many of his adoring patrons. He spoke several languages in varying degrees of proficiency, such as English, Tamil, Hindustani, Gujarati, Marathi, and even some German. His close links with the royal house of Travancore distinguished him from the legions of nameless artists and painters in India. To his credit, Ravi Varma did not rest idle with the rewards of his fame. He succeeded in taking his art into the homes of millions of Indians through a popular lithograph press, despite grave financial losses, and gave dignity to the profession of painting. Unlike Indian artists before him, whose identities are largely lost to posterity, he signed his name on his work with pride and confidence, imbuing the entire craft with those qualities. That is also why, when he died in 1906, people from many walks of life mourned him with creditable sincerity. He was not exceptionally wealthy (‘Had brother taken care to save the money he had earned by painting, he would have been one of the richest men,’ a sibling regretted),5 but left behind, in the admiring estimate of a contemporary, a name and legacy on ‘fame’s lofty pinnacle’.6

Yet this path to glory and greatness was not easy for Ravi Varma, and in his marriage to art much else had to be sacrificed. For a few years after his arrival in 1862 at the durbar, he was engaged mainly in self-study as the other artists, with all their internecine rivalries, refused to guide or assist him in any way. ‘What really sustained him during these years,’ one biographer writes, ‘was his will to break through and excel, and an abiding faith in divine grace.’7 Tenacity was definitely a pronounced feature in the boy, but Ravi Varma did have a few other tricks up his sleeve than entrusting the matter entirely to divine offices. When the proud Ramaswami Naicker refused to initiate him into oil painting, he succeeded, most likely by underhand inducements, to persuade Arumugham Pillai, one of Naicker’s apprentices, to give him secret lessons by the darkness of dusk. With all the watchful distrust among court painters, it was no mean accomplishment for the young boy to orchestrate a clandestine arrangement with none other than the trusted pupil of the biggest notable in Trivandrum’s clannish art circles. An ingenious wit and a perfectly comfortable approach towards manipulation in the attainment of his own artistic ambitions were also, then, unabridged features of Ravi Varma’s fascinating personality.

In 1868, however, a new chapter began in his life when a sensational character arrived at court in the form of Theodore Jensen. He was a Danish painter of no great ability but whose flawless white skin opened him many princely doors in the East. ‘It was not,’ says E.M.J. Venniyur, ‘uncommon with European portrait painters of those days, who were probably none too successful at home, to come to India and extol in gold and velvet … the Maharajahs wreathed in oriental splendour.’ The Maharajahs, for their part, were equally enthusiastic to entertain Europeans, ‘for these were times when the elite of the country cultivated British tastes most assiduously’.8 Jensen got down to business and Ravi Varma promptly sought the honour of becoming his student, no doubt eager to learn from a bona fide ‘master’. The Dane, predictably enough, was no less unwelcoming than Naicker and the others, aware, as he was, that he too came only with the dubious distinction of oil painting with a white hand. At the Maharajah’s insistence, though, Ravi Varma was reluctantly granted permission to watch Jensen at work. And as it happened, the boy, now aged twenty, decided he would one day give these haughty artists, Indian and foreign, a run for their money.

By 1870, Ravi Varma was able to acquit himself in oil painting with much promise and intuitive flair. But a new set of problems arrived as friends and relations realised he intended to make a living out of art. The Varmas in Kerala were an aristocracy steeped in meticulous ceremony and endless ritual that built around them an aura they much enjoyed. They were once a ruling class and even in the late nineteenth century controlled vast swathes of land, keeping memories of bygone times alive through their traditions and antiquated way of life. There was, in 1870, no precedent of any of them having worked at all, leave alone working as a painter, which was seen more as a profession of lowborn artisans. In the face of opposition, however, the Maharajah came to Ravi Varma’s rescue. Declaring that art was divine, he gave the painter his blessings and wholehearted encouragement. Reinvigorated by royal support (and the attendant silencing of the conservative faction), Ravi Varma went on a forty-one-day pilgrimage to Mookambika and propitiated the goddess Sarasvati. On his way back, in what was seen as a good omen, he received his first paid commission from a High Court judge in Malabar, the northern portion of Kerala, once the domain of the Zamorin and now under direct British administration. He was hereafter officially a professional painter.9

Back in Trivandrum the talented Ravi Varma now commanded the complete attention and support not only of the Maharajah but also of his singularly attractive consort, Kalyani Pillai. This was a woman of tremendous personality, and a mind of her own, that often upset more orthodox sections at court. Born in 1839 as a subject of the neighbouring Rajah of Cochin, she was the only daughter of a former minister there, and a consummate mistress of all the cultural refinements of her class. She arrived in Trivandrum quite unexpectedly sometime in the 1850s, with scandal in hot pursuit. For local gossip has it that she had eloped, in a rather unladylike fashion, with a famous actor called Easwara Pillai, a member of the palace drama troupe.10 At some point the Maharajah became acquainted with her and fell in love, so that in 1862 she dissolved her marriage to Easwara Pillai and became the ruler’s consort.11 Slowly a coterie of young intellectuals, artists, musicians, and others began to revolve around her, a fine poet and composer of Sanskrit plays herself, and her obliging husband. She went on to learn English, even interacting with Christian missionaries and reading the Bible, with an urbane irreverence that at once attracted and infuriated less liberal souls outside her ring. Ravi Varma, now a member of the elite inner circle of the Maharajah and his enigmatic consort, became so close to her that some even hint at a romantic liaison.12 In any case, after his return to Trivandrum in 1870 he executed a portrait of the royal couple, which was close to such remarkable perfection that he was instantly elevated as a favourite. The Bangle of Honour (called Veera Srinkhala) was awarded him, no mean distinction for a painter, and for the next decade the Maharajah and Kalyani Pillai unstintingly championed Ravi Varma and his art, giving him the wings he needed to flourish.

Naicker, of course, did not appreciate his own fall from royal favour and the introduction of Ravi Varma, with all his personal rapport with the monarch, into that coveted spot. In 1873, both sent their paintings to the Fine Arts Exhibition sponsored by Lord Hobart, the Governor of Madras. Ravi Varma not only won the Gold Medal, but his Nair Lady at the Toilet was ‘much admired’ and is said to have become ‘the talk of the town’.13 In the same year he sent the painting to an international exhibition in Vienna, winning another medal that brought him coverage in all major newspapers of the day. In 1874 and 1875 he won Gold again in Madras, and his work was offered as an official present to the visiting Prince of Wales, a serious honour at the time for so young a ‘native’ artist. By 1876, the Governor of Madras was collecting his work, and his Sakuntala’s Love Letter was sought by Sir Monier Monier-Williams as frontispiece for his famous translation of the Sanskrit Abhijnana Sakuntalam. Soon after this, in what a bitter Naicker only viewed as another testament to Ravi Varma’s audacity and arrogance, the star artist declared that he would no longer compete for prizes and would only exhibit his work at public platforms. By now he was a popular member of Madras society, and an established painter with very pleased royal patrons in Trivandrum. Nothing could, it seemed, halt the meteoric ascent of Ravi Varma into the towering heights of history.

In 1880, however, all this began to unravel and Ravi Varma was to shortly be cast adrift. The reigning Maharajah, Ayilyam Tirunal, died unexpectedly after a brief ailment only to be succeeded by his staid, colourless brother, Visakham Tirunal, who was more a botanist than a connoisseur of the arts. For years there had been no love lost between these siblings, and one of the first acts of the new ruler was to dismantle the palace establishment, comprising his late brother’s favourites, replacing them with his own loyalists. Naicker, interestingly, was one of the new Maharajah’s partisans, and Ravi Varma realised his position was now untenable. In 1881 there was a public falling out between him and the Maharajah during a state visit by the Governor of Madras. Lord Buckingham considered Ravi Varma a friend and asked to see him during his meeting with the ruler at the palace. Visakham Tirunal had the artist summoned but was livid when he saw the Governor receiving him with a warmth and familiarity that he had not shown him. When Buckingham invited Ravi Varma to join them, the meeting turned awkward, for according to the dictates of court etiquette, the artist could not sit down in the presence of the Maharajah. The entire discussion had to be conducted with all three men standing, and the protocol-obsessed Visakham Tirunal became more and more incensed with every passing moment. He was furious that a subject of his should be seen as an equal and that he should have the temerity to publicly act friendly with a visiting dignitary, demeaning the Maharajah who could but swallow his pride. The story goes that the very next day Ravi Varma left Trivandrum, never to return during the reign of the hateful Visakham Tirunal. This may well be apocryphal but there was certainly a quarrel followed by the artist’s unceremonious departure from court in 1881.14

But the ever-resourceful Ravi Varma only turned calamity into opportunity as usual. Determined to continue his work with or without royal backing, he now left for Bombay. Making full use of the many contacts he had made in Madras over the years he found new vistas of patronage and help. The Maharajahs of Baroda and Mysore gave him important commissions and soon he was able to build up a formidable reputation across India that brought him only more acclaim, while old Naicker and the wrathful Maharajah continued to fret and fume in Trivandrum. His stipend from the durbar was cut off and attempts were made by Visakham Tirunal to have him ostracised from his caste. Again Ravi Varma, who knew he was in a different league now, managed to foil this through his influential friends.15 By 1904 the Viceroy of India, on behalf of the King of England, awarded him the Kaiser-i-Hind, a distinction that his first patron Ayilyam Tirunal had once received, truly elevating the artist to equality with his royal sponsors, no matter how much the latter resented this. He was now known popularly as Raja Ravi Varma and, to add to his prestige, in 1903 he also succeeded as head of the Kilimanoor family, making him a leading figure of the Malayali aristocracy. By his fifties, thus, Ravi Varma, the country boy who had come to Trivandrum with oil paint on his adolescent mind, was firmly at the pinnacle of worldly success, while those who stood against him faded into history or respectable oblivion.

While Ravi Varma earned himself a place among the great personalities of India, in Trivandrum, Ayilyam Tirunal’s glamorous widow was fated for a joyless eclipse from public imagination. With the death of her husband, the bewitchingly beautiful and talented Kalyani Pillai was disengaged, in keeping with tradition, from all society, and prohibited further unorthodox cultural pursuits.16 A ‘liberal provision’ was granted from the state treasury for her ‘maintenance in comfort and dignity’,17 but she was for all real purposes restricted in her residence as was conventional with royal widows in Travancore. Occasionally her irresistible appetite for life saw her mildly breaching the rule, as witnessed, for instance, during Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee celebrations in Trivandrum in 1887, when she sent felicitations to be read out at a public durbar. But for the most part she had mellowed, and disappeared prematurely into the twilight of her life, which came to an end at two o’clock on 18 January 1909, nearly thirty years after her beloved Maharajah had died.18

Kalyani Pillai, for all her inner magnetism and strength of personality, always knew her life was destined to conclude in this manner. For under the matrilineal law of succession prevalent in Kerala, even though she was married to the ruler, she was not his queen. On the contrary, she was merely his consort, whose status was by no means set in stone. She lived at the Maharajah’s favour, and could easily be discarded if he tired of her or preferred a new candidate as his partner. Indeed, Ayilyam Tirunal, while highly regarded for his perspicacity and for laying the foundations of modern government in Travancore, was personally ‘notorious as a moral wreck’, with ‘a flood of local stories prevalent about his perversions’.19 It was to Kalyani Pillai’s credit that she not only retained the official position of consort for herself, but also succeeded in adopting children with the Maharajah when she could have none of her own. But this pre-eminence was still enjoyable only during his lifetime, and after his death she had to invariably reconcile to uncomplaining anonymity, making way for Visakham Tirunal’s preferred spouse. Even her official title as the wife of a Maharajah of Travancore was not Rani but Ammachi, which as a 1912 feature in London’s The Lady pointed out, merely meant, ‘The mother of his children’. Nobody could have stated the fact more succinctly:

Whenever a stranger goes to Travancore, one of the largest and most picturesque native States, situated in south-western India, they always tell him not to address her as ‘Your Highness’. They think this word is too dignified to apply to her. No doubt she is the Ruler’s spouse; but that does not make her the Maharani or even the Rani. She is only Ammachi, just the mother of His Highness’ children, and they believe that word is good enough to express her relationship to the man who is autocrat of more than 2,950,000 people, inhabiting [over] seven thousand square miles of territory, yielding an annual revenue of about £700,000.20

In a similar manner, the sister-Ranis also selected nobles of superior caste as their partners, and these gentlemen, chosen invariably from Ravi Varma’s clan, were equally disposable at will. Fancy titles were granted them but never any real power or royal status, and they were expected mainly to serve their wives by fathering the next generation of the dynasty. Indeed, as late as the 1920s, the Ranis’ husbands were ‘entitled only to a monthly allowance from the durbar of Rs 200 per mensem with meals from the palace and the use of a brougham and pair of horses’.24 Even into the 1940s, at grand banquets, while the Ranis and their children would be served four varieties of dessert, the consorts were entitled to only two, while ordinary guests had to satisfy themselves with a single option.25 Custom discouraged them from living with the Ranis, and they had to await royal summons whenever their wives wished to entertain them. Indeed, they were disallowed even from travelling in the same carriage as the Ranis, and if due to any reason they had to, it was essential that they sat opposite and not next to their wives.26 In public they had to bow to them and refer to them always as ‘Your Highness’. They were certainly fathers of Maharajahs, but in the matrilineal system it did not matter who your father was, as much as who your mother and uncle were. To those more accustomed to the patriarchal tradition, all this seemed rather outlandish and perhaps even unnatural. But as the writer in The Lady wistfully remarks, these sons and husbands were ‘used to this sort of procedure from long centuries of customary practice’ and would say with ‘smiles playing upon their lips’ that they were meant to be private citizens, even if they were born or married to royalty.27

The Travancore dynasty, however, was not really known for its fecundity and historically there was always a lack of girls born of blood royal. The family produced males in healthy abundance, but usually with fewer sisters to continue the line. Since the fourteenth century, in such instances it was customary to adopt girls from another old family in Kerala and install them as Ranis in Travancore, with their sons taking the dynasty into the next generation. These adoptions were always made from the house of the Kolathiri Rajah of Cannanore. Once a proud prince in Malabar (though nowhere as grand as the Zamorin), this was a Rajah who used to lord over a thriving port and, like all petty potentates worth their salt, flaunted a fanciful pedigree from ancient dynasties and mythical kings not to speak of the sun, moon and other heavenly entities. In other words, the Kolathiri line was equal in stature to Travancore’s, and their females were eminently qualified to replace the latter’s Ranis. In fact, Ayilyam Tirunal and Visakham Tirunal themselves were descendants of one such royal adoptee who was brought in from Cannanore and installed as Rani in 1788. By this time, however, the Kolathiri Rajah’s circumstances were rather appalling, and his family had swollen into several unwieldy, quarrelling branches. Its members, in the words of Canter Visscher, ‘both male and female, [were] so numerous that they [lived] in great poverty for the most part’.28 To add to their agonies, soon after 1788 they were forced into exile and had to abandon their ancestral lands altogether, when the fearsome armies of Tipu Sultan of Mysore routed their feeble defences and overran all of Malabar. Eventually the English East India Company annexed the region and most constituents of the no-longer-royal Kolathiri dynasty accepted the invitation of the Maharajah of Travancore, their affluent and still afloat relative, to settle in his state, where estates, pensions and the offer of a better life were placed at their grateful disposal. They were accommodated in various parts of the principality, with one division of these immigrants establishing themselves in the town of Mavelikkara, a hub of the pepper trade in bygone times.29